SCM Analysis

Detailing

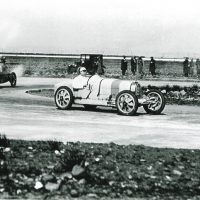

| Vehicle: | 1925 Bugatti Type 35 Grand Prix Two-Seater |

| Years Produced: | 1924–30 |

| Number Produced: | 96 |

| Original List Price: | Unknown |

| SCM Valuation: | Median price to date, $975,000; high sale, $1,650,000 |

| Tune Up Cost: | $1,000 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Brass tag on left firewall, also on engine |

| Engine Number Location: | Left rear mounting flange on block |

| Club Info: | American Bugatti Club |

| Website: | http://www.americanbugatticlub.org |

| Alternatives: | 1928–35 Mercedes-Benz SS Roadster, 1928–32 Mercedes-Benz SSK, 1927–31 Bentley 4.5 Litre |

| Investment Grade: | A |

This car, Lot 118, sold for $1,200,618, including buyer’s premium, at Bonhams’ “Les Grandes Marques à Monaco” sale on May 14, 2016.

The Type 35 and its variants are arguably the most iconic of all Bugattis, and they also are subject to probably the widest range of market values of any pre-war collectible car, depending on authenticity, originality and completeness.

You can buy a completely fake Argentinian replica for about $230,000. You can probably find one with some original 1920s French components finished out with aftermarket parts for around $750,000, or you could take about $5 million and try to extract one of the five or six remaining perfect original ones from the arms of their current owners. The variation is that great, and in honesty, it’s there for a reason. Let’s consider why.

The many variants of the Type 35

One of the primary reasons that the Type 35 is so iconic is that Bugatti built an awful lot of cars that looked just like it, so knowing what the variants are is an important place to start. The original Bugatti Type 35 used a 2-liter SOHC straight-eight engine with normal induction and a five-bearing crankshaft using roller bearings on both mains and rods.

The Type 35C is a supercharged version of the 35.

The Type 35A was the same car, but with a far simpler 3 plain bearing engine, much less power and a lower price tag. It gained the nickname “Tecla,” after a maker of imitation jewelry, and was not widely loved then (or now).

The Type 35T was a 2.3-liter aspirated version specifically for the Targa Florio race.

The Type 35B is a supercharged version of the 2.3-liter T that was raced when the 2-liter displacement cap didn’t apply.

The Type 37 has the same chassis and body, but with a 1.5-liter, 4-cylinder engine making 60 hp. There were lots of these (290) built, including 67 Type 37As, which were supercharged.

The Type 39 was identical to a 35C, but the 8-cylinder engine was de-stroked to 1.5 liters for class racing. All in all, Bugatti produced something like 645 cars that were variations on the theme.

Key factors to consider

The three important points to remember when considering all this are:

Bugattis were wonderful and fast but tended to be a bit fragile.

Except for the 35A, most of these cars were raced hard, at least until World War II interrupted things.

Most of the mechanical parts of all 645 cars were easily interchangeable.

The general result of these facts was that parts from various broken cars ended up being incorporated into ones that were still running. More particularly, parts from lesser and unimportant cars tended to migrate to the ones that were still winning.

After World War II, a cottage industry sprang up to supply the bits that could no longer be cannibalized, and eventually it became possible to have a Type 35 with no parts that were of French manufacture — or more than 10 years old. For purists and serious collectors, this is a travesty. The importance of having components that were originally delivered on a car cannot be overstated.

A collectible treated like an old racing car

Around my restoration shop there is a standard complaint: “All right, who took this wonderful, irreplaceable, museum-worthy piece of automotive history and treated it like it was just an old racing car?”

Unfortunately, that is what virtually all of them were. Our subject car was originally delivered to the very famous driver Glen Kidston, and it then passed through various hands and lots of racing until 1937, by which time it was an old — and not competitive — car sitting in the back of a shop outside London.

A teenaged Australian named Lyndon Duckett had been in Europe unsuccessfully looking for a later twin-cam Bugatti. When he couldn’t find anything, he bought this car, had a 1.5 liter twin-cam Anzani engine installed, and shipped the car to Australia, leaving the original engine and bodywork in the U.K. (Australian customs duties were punitive, but could be largely avoided with no body on a chassis).

The Anzani Bugatti

In its new home in South Australia, the car got a new body with more rounded contours and quickly became very well known in Australian racing as the “Anzani Bugatti.”

Duckett raced the car actively for about 10 years, and then took to running it in the new “vintage” events before selling it on in 1962. In 1964, it passed to another Australian, Bob King, who kept it for the next 52 years and used it extensively.

In 2006, having accumulated some of the required parts, he embarked on the process of removing the Anzani engine and returning the car to its original specification. Aside from an original Type 35C sump and various minor components, the new engine comprised new castings and parts. The bodywork and wheels were also new. In its new/old all-Bugatti configuration, the car saw epic use — around Tasmania and round trips across Australia, from east to west and south to north, all with utter reliability. This car got used.

Careful maintenance and loving care can forestall aging indefinitely for old cars, but humans aren’t so lucky. So it became time to find a new home for the Bugatti.

The engine and mechanicals were rebuilt and it was sent back to its ancestral home to find a new life — hopefully in the garage of a serious collector. Given the car’s early history in the hands of patriarchs whose families are still in the collector business, the likelihood of it finding a proper home was high. The issues revolved around where the market would value it. In the circumstances, an auction was the perfect venue to resolve the question.

Great provenance, middling mechanicals

The basic conundrum in setting a value was that the car scored very high in factors such as history and provenance. It has a great racing history, an unbroken and loving ownership chain with a very few long-term residencies, and enthusiastic and reliable use over the years by Bugatti devotees.

However, the car scored low on type desirability and mechanics. Type desirability has to do with it being a Type 35 and not a 35C, as everybody wants the supercharged cars if they are spending big money.

Mechanics scored low simply because the car didn’t have its original engine, or, for that matter, any original engine. A new replica engine may work wonderfully and look right, but it kills collector value.

The original engine is not lost, as it moved to another Type 35 and is well known in Bugatti circles, but its absence in this chassis probably cut the value in half. Repatriating that engine to this chassis would be of immense value, but without a suitable original Type 35 engine to use as trade stock, the negotiations are likely to be difficult.

Back to the family

As suggested earlier, when the car went across the block, there was little question about whether the car would sell — or even to whom. The only unknown was the price. I wasn’t there to observe the bidding, but I would guess that in the early stages there were opportunistic bidders willing to buy this car with both its great provenance and compromised mechanicals — if the price was attractive enough.

Once it became obvious that there was a committed and qualified buyer who was planning on taking it home — and the price got above bargain levels — the opportunists dropped out and the car sold for very close to low estimate. I imagine that the seller was a bit disappointed, but it was a difficult car to sell.

I would say the car was fairly bought. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Bonhams.)