SCM Analysis

Detailing

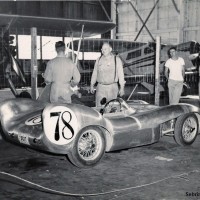

| Vehicle: | 1955 Lotus Mk IX Competition |

| Number Produced: | About 30 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Unknown |

| Engine Number Location: | Right side of block at front |

| Club Info: | Club Lotus |

| Website: | http://www.clublotus.co.uk |

This car, Lot 263, sold for $182,789, including buyer’s premium, at the Artcurial Paris auction on June 10, 2013.

All of the great post-war racing marques have their creation myths — or at least origin stories — and they mostly are based around great individuals who, having shown brilliance before the war as team managers (Ferrari), engineers (Porsche), or industrialists (Sir William Lyon of Jaguar and David Brown of Aston Martin), used the power, experience and money that they had accumulated to create or build formidable racing entities as Europe’s economies recovered during the 1950s.

Lotus wasn’t like that at all. Colin Chapman and the group of friends he assembled to build the cars he called Lotus were a motley group of barely 20-year-old kids who had come of age shortly after the war. None of them had any experience in the automobile business (or in anything else) beyond repairing their own pre-war Austins. Several had trained as engineers, but they were mostly just car nuts. They all had other jobs. None of them had any money, although two brothers named Allen had indulgent parents who provided a well-equipped garage and occasional financial help in the earliest days.

What they did have was energy, enthusiasm, intelligence, and a willingness to work insane hours on evenings and weekends in pursuit of their dream, which in the beginning was simply to build some racing cars for themselves. And of course they had Colin Chapman. Suave, persuasive and charming — as well as egotistical and very manipulative — Chapman had the perfect combination of attributes to assemble and motivate a small group of volunteers to effectively build him a racing car.

Trained as a civil engineer, Chapman had an excellent feel for structures and developed the first Lotus, a modified Austin Seven mud trials/road car, while in the RAF during the late 1940s. He learned that a light, stiff chassis with soft suspension in a very small car managed the dual roles very well. In June 1950, he took it to the Silverstone circuit on a lark and beat a serious Bugatti, proving that his ideas worked on the track as well — it also hooked him on circuit racing.

Chapman was now out of the RAF, and the 750 Motor Club had announced a new class of sports racing cars based on Austin Seven mechanicals, so for the 1951 season he was determined to build a car to compete. This is where the team of volunteers entered the scene.

Fast from the start

Working in the garage behind the Allens’ house, the friends took to building the first “frame-up” Lotus, the Mk III, and it was ready to race in May. It was an immediate success. Very quickly, the other competitors came knocking, looking for all manner of pieces and services.

By December 1951, they had to move out of the garage and into proper commercial space: Lotus Engineering became a real company. In July 1952, the space-frame Lotus VI was introduced — the first Lotus sold to customers — and the lads started thinking that they might actually become a car company.

By early 1954, Lotus had sold a few Mk VIs and wanted to step beyond British club racing and try their hand in the 1,500-cc International Class, where Porsche and OSCA dominated. It was time for the Mk VIII. All previous Lotus cars had looked essentially the same: a rectangular body with front cycle fenders and faired-in rear wheels — much like the J Allards, only smaller — but to go up against European heavyweights a proper streamlined body was essential.

One of the original crew was Mike Costin, who had gravitated into being the engines guy as Lotus developed. His older brother Frank was an airplane designer for de Havilland, so it seemed a good idea to take the body design project to him (as an aside, the catalog copy quoted above is incorrect — Mike Costin ended up being the “Cos” in “Cosworth”, while Frank, an aerodynamicist and structures guy, eventually became the “Cos” in “Marcos”). Although (or maybe because) he had never dealt with automobiles before, Frank accepted the challenge (for free in his spare time, of course).

Frank Costin was particularly concerned — even alarmed — with the prospect of somebody on the ground going 130 mph in a vehicle as light and small as Chapman proposed. So, he spent an inordinate amount of time creating a low-drag shape that would be extremely stable at speed. The resulting design was spectacular — particularly at the time: a low, very pointy nose that rose in curves to a pair of almost tail-like rear fenders that were designed to prevent yaw at high speeds. It wasn’t a stylist’s dream; it was pure aerodynamics — and it worked.

Lighter and faster

The prototype Mk VIII, with an MG engine, was an immediate success, and Lotus quickly started building them for customers. In a fortuitous coincidence, the Coventry Climax company, a builder of forklifts and industrial engines, had recently introduced a very light marine fire-pump engine and had been persuaded to modify it for automotive use. The Climax FWA (Feather Weight Automotive) became available in mid-1954 — just in time for the new Lotus.

Considering the cast iron, pre-war lumps that were the alternative, the Climax FWA was a revelation: light, powerful and small. It was a perfect match for Lotus racers and became their standard engine. Only a few Lotus Mk VIIIs were built: The car quickly evolved into the Mk IX — the first Lotus to use standardized components.

Strong in history, less so in price

The Mk IX was the first “production” Lotus, and as such, it holds a particularly important spot in the pantheons of both Lotus and of British racing in general. The current British hegemony in racing design and production got its start with the success of Lotus. Where it fits in the pantheon of collectability is a more complex question.

Although it was hugely important in both design and execution, it was always more of an everyman’s racer — a David among Goliaths — and the basic rule of “special then, special now” seems to apply. Based largely on production-car components ingeniously adapted to the purpose, it was built for and sold primarily to struggling Englishmen trying to recover from the war, and it sold for a fraction of what equivalent Porsche, OSCA, or Maserati racers (with almost exclusively bespoke components) cost. Lotus proved that it could — indeed still does — easily run with the big dogs, but it lacks the prestige of racers built for rich sportsmen. So, now as then, Lotus cars carry a fraction of the value of those big-dog cars.

The best comparable car to the Lotus IX is the Lotus Eleven, The IX is more historic — and more rare — so it is more collectible than the Eleven. However, the IX is not as fast or as comfortable to drive, so it has less value as a racer. These factors seem to balance out in a manner that leaves the two roughly equivalent in value, with the Eleven slightly higher at just under $200,000. Our subject Mk IX was set up more as a racer than a collectible (incorrect disc brakes) and thus suffered some in relative value. I would say it was correctly bought and sold. ?

(Introductory description courtesy of Artcurial.)