SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1966 DeTomaso Vallelunga |

| Years Produced: | 1964–68 |

| Number Produced: | 53 |

| Original List Price: | Unknown |

| SCM Valuation: | $100,000–$150,000 |

| Tune Up Cost: | $475 |

| Distributor Caps: | $30 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Stamping on frame member right rear corner of engine compartment, data tag in front compartment on bulkhead |

| Engine Number Location: | Intake side of block |

| Club Info: | None |

| Alternatives: | 1960 Porsche 356 GTL Abarth, 1964 Matra Djet II, 1964 Alfa Romeo Giulia SS |

| Investment Grade: | C |

This car, Lot 65, sold for $256,942 (€226,480), including buyer’s premium, at the Artcurial Automobiles sur les Champs sale in Paris, France, on June 22, 2015.

I wrote not long ago here in these pages a profile of the DeTomaso Mangusta (October 2012, “Etceterini,” p. 42). My comments began with: “The Mangusta is one of those cars that has a reputation. The kind of car you might like to take out for a long, hard ride on fast empty roads, but afterwards you wouldn’t want to drive home to see your parents.” Alejandro DeTomaso’s first production car, the Vallelunga, isn’t well known enough to have a reputation, but if it were, it would certainly be a more socially acceptable one than its younger sister.

While the Mangusta is striking, sexy — even a bit threatening in appearance — the Vallelunga is petite, elegant, simple and beautiful, a well-integrated shape with lovely small details. It looks like a light, fast sports car, which is exactly what was intended. It’s undeniable that Giugiaro’s design has a certain kinship with another of the most beautiful sports racing cars ever, the Porsche 904, of which it was a contemporary.

Both appeared in 1963 and were lightweight, fiberglass-bodied coupes with steel structures. From there they had little in common, mainly due to the fact that the almost agriculturally basic 1.5L Ford Kent engine in the Vallelunga gave away 94 horsepower to the wickedly complex four-cam flat 2L engine of the 904, which also, according to manufacturer specifications, weighed almost 200 pounds less than the 1,500-pound Vallelunga.

So it was clear to a competitive type such as DeTomaso that for his next car either the weight had to be reduced even further or the power had to come way up. The successor to the Vallelunga, the Mangusta, is certainly no lightweight, tipping the scales at a portly 2,600 pounds, but the power was tripled by the Ford 302-ci V8 that pumped out 300 horsepower.

Busting myths

While the Vallelunga may be too unknown to have developed a rep, nonetheless a good number of “accepted facts” have crept into general belief — much like the supposed “dangerous undrivability” of the Mangusta.

Here, it’s the thought that the Vallelunga’s chassis was so weak that it couldn’t handle even the fairly anemic grunt of the Kent lump, so it could bend itself into a pretzel if you pressed too hard on the road or track. Also, it is supposedly so loud and buzzy inside that driving it is reminiscent of being at an AC/DC concert inside a steel drum.

This is a car that doesn’t have to have tons of excess power — but one that wins the day with a balance of handling and superb visibility. It’s certainly not Lexus tomb-like inside, but anyone who buys a mid-engined 1960s coupe to listen to the radio and balance a quarter on edge on the console is rather missing the point.

Of course, the captivating styling also makes it quite appealing. It’s a car I could spend as much time enjoying looking at as driving. That it is truly rare also helps explain its appeal, although it’s also clear that DeTomaso had no intention of it remaining quite so rare and would have loved to have built many more. If you want a Vallelunga, you have to find them where and when you can.

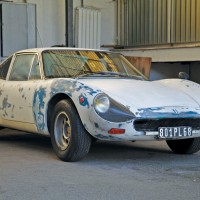

A project car

Our Paris car was an ambitious project for anyone considering it — and a great example of why “original” is a word that can mean many different things to people. Generally speaking, when a vehicle is sold in the middle of the restoration, a considerable discount is to be expected compared with an untouched original or an expertly restored example. Why? Because in the other cases, you know what you’re getting — a factory complete car as built and maintained, or one which has had all of its original finishes and systems rebuilt or replaced to factory standards.

It has been posited that the remarkable result achieved for this ambitious project is due in no small measure to the impressive increase in Mangusta values in the past few years. While awareness of DeTomaso’s pre-Pantera output has certainly grown, and Mangusta values have certainly more than doubled in the past five years, I don’t think this is a case of rising tides lifting all boats. Vallelunga prices have exploded four-fold in the same timeframe. The person who is drawn to a Vallelunga is a different character altogether than Mangusta Man. The appeal here is not of raw power or intimidating road presence. The Vallelunga is a rapier rather than a cudgel.

Here, the paint was stripped — that’s good, as the condition of the fiberglass could be assessed. But it goes downhill from there.

The door fit appeared to be a bit out of line at the sills on both sides, and the rear side quarter windows were missing, replaced with strange louvered panels. Just what were they intended to cool? The occupants’ heads?

Not only were the windows gone, but so were their frames and opening hardware. Inside, the correct original gauges were in place, but the wood grain on the dashboard had been painted over and worse still, the metal shift gate had been crudely cut away. The steering-column cover was missing, as were all traces of floor or console trim. No mention was made in the catalog description of additional parts which came with the lot. Hopefully, the polished-alloy rear grille-surround body trim had only been painted black.

Perhaps the biggest challenge to this Vallelunga was the stated ID number. All the Ghia-built fiberglass production cars have four-digit chassis numbers that begin with “VL.” The chassis number as listed in the catalog seems to be the engine number, consistent with the seven-digit IDs of the Kent engine. Efforts made before the sale to find the actual chassis number were unsuccessful, and as of the time of writing the answer is still unknown.

Underwater for now — but not forever

Speaking with collectors who have long experience with these cars, it was agreed that it would conservatively require $100k to $175k to bring this example back to where it deserves to be. As the best restored Vallelungas have sold for $175k to $225k, it seems as if this buyer might expect this model to appreciate into Mangusta $300k territory. It’s not impossible, but this purchase was hopefully made for emotional rather than financial reasons.

The seller did extremely well here — make no mistake. But when you’re after one of 50 of anything, you have to get an example when you can. The buyer succeeded in obtaining something that most of the rest of us still don’t own: a DeTomaso Vallelunga. ♦

(Introductory description courtesy of Artcurial.)