In total, 1,258 1.6 HFs were built during 1969–70, of which approximately the first 600 were designated HFS and fitted with the Variante 1016 engine featuring modified cams similar to the Works rally cars. This car, 001578, which is a rare fanalone (big-headlight) version, is one of the last HFSs to be built and is contemporary with cars used by the Works in late 1969/early 1970. Believed to have been used as a reconnaissance car by the Works team, it still has various Works parts including inlet manifolds, 45-mm Dell’Orto carburetors, 10,000-rpm tachometer and Abarth steering wheel, although the 1016 engine has been replaced.

The Fulvia stayed in Italy until the mid-1970s before moving to Belgium and eventually the U.K., where it competed in historic rallies until the early 1990s. In 2000–03 it underwent a lengthy restoration.

The car has been returned to Group 4 specification with aluminum panels, magnesium alloy wheels, race/rally-prepared engine, 5-speed competition gearbox, foam-filled long-range fuel tank, FTA six-point roll cage, FIA seats and harnesses, fully plumbed fire extinguisher, master cutoff switch and Plexiglas windows.

This car is eligible for the Targa Florio, Milano-San Remo, Tour Auto, Monte Carlo Historique and many other prestigious international events — as well as series such as Top Hat and HSCC. The Fulvia has won several prizes for presentation, including 1st place in the RAC Club concours at Woodcote Park in 2004, and it has been featured in several motoring magazines, most recently Auto Italia in 2004. It is offered with RAC/MSA papers, U.K. V5C registration document and an expired MoT certificate (2006).

SCM Analysis

Detailing

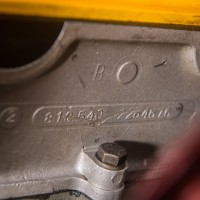

| Vehicle: | 1969 Lancia Fulvia Coupe Rallye 1.6 HFS |

| Number Produced: | 1,258 |

| Original List Price: | $5,200 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Plaque in engine bay |

| Engine Number Location: | Flywheel ring above starter |

| Club Info: | American Lancia Club |

| Website: | http://americanlanciaclub.com |

This car, Lot 512, sold for $70,101, including buyer’s premium, at the Bonhams Paris sale on February 7, 2013.

Virtually nobody in the United States understands Lancias, but in Europe — particularly during the early post-war years — the company enjoyed almost cult status.

The saying at the time was: “Fiat sold cars to the masses, Alfa Romeo sold cars to the sportsmen, and Lancia sold cars to the connoisseurs.” Lancia was a broadly based automotive manufacturer with commercial and military vehicles as well, but their cars defined the company.

Their specialty was very high-quality small-to-mid-sized cars with state-of-the-art technology — with enough flexibility to build short runs of almost custom variants of their basic models to meet the expectations of a connoisseur customer base. It was a unique niche-marketing strategy that had served the company well but was completely unsuited to the U.S. market, where Lancia remained almost completely unknown.

Winning races — but not profits

In the mid-1950s, Lancia found itself in a situation of glorious failure.

It was glorious because their chief engineer, Vittorio Jano — who had been recruited from Alfa Romeo just before World War II — had immediately after the war created a series of fabulous automobiles, particularly the Aurelia, and had taken Lancia to the heights of international auto racing.

It was failure because everybody loved the Aurelia and stood in awe of its technology, but few people bought them — and because winning the Carrera Panamerica with Fangio in the D24 and creating a dominant Grand Prix car with the D50 in 1954 was wildly expensive. Sales of their 1,100-cc Appia sedan were excellent, but it couldn’t support everything else, and the company staggered into insolvency.

The sale of the company to an Italian concrete magnate saved Lancia. Trouble was, the concrete tycoon immediately replaced the racing genius Jano with a professor who hated racing: Antonio Fessia (Vittorio Jano moved to Ferrari, where he achieved greatness, but that is a different story).

Aside from feeling that competition was a waste of time and money, Fessia’s great conviction was that, although all Lancias to date had been rear-drive, the future of the automobile was front-wheel drive. After some engineering housekeeping to keep the existing cars modern, he and his engineers set to designing a FWD future for Lancia.

They started with a mid-sized (1,500-cc to 2,000-cc) flat-four powered platform that became the Flavia. Then they set out to replace the company’s most popular model: the 1,100-cc Appia. The Flavia was introduced in 1961, and it was an immediate success, so creating a smaller version made both manufacturing and marketing sense.

The original approach was to mate the Appia V4 engine to the Flavia FWD assembly and mount it on a much shorter chassis — and thus the Fulvia was born.

It was never that simple, of course. The Appia V4 was hopelessly out of date, so an entirely new engine was designed: an 1,100-cc unit with a narrow angle between the cylinders and a very wide, twin-cam cylinder head covering both banks.

To make a compact, low package that could hide in front, the engine was laid over 45 degrees and a unique transaxle was designed. When it was presented to the world in 1963, Fessia’s pragmatic approach had created a 4-door sedan with the charisma and excitement of a cereal box, but the mechanical package was awesome.

As a connoisseur’s car, Lancias had always appealed to wealthy sportsmen, and with the burgeoning economy of the early post-war years, the Aurelia had found substantial favor with the rally crowd.

A quick note here: European rallying is not anything like the tame “time/distance” version popular in the U.S. It is a wild and woolly serious competition — but in licensed road cars on open roads.

The weapon to have

The earlier Aurelia, with the world’s first production V6 mated to the first production transaxle, had made a superbly balanced rally car and had become the weapon to have, certainly for an Italian in the ’50s. Fessia’s disdain for competition didn’t stand a chance against the resulting loyal Lancia customers, so the company started taking care of them.

In 1960 Lancia formed a club for these loyalists, calling it “Hi Fi” — for high fidelity to the marque — and began more actively supporting their activities. Thus, the term “HF” entered the Lancia nomenclature, meaning the competition-oriented cars.

As I mentioned earlier, producing variants was a Lancia specialty, and there were 24 distinct series and models of the Fulvia during its 10-year production life. One of the first was a svelte little sporting 2-door, the coupe, and the hot-rod rally version that soon arrived was, logically, the Coupe HF. The original 1,100-cc engine could be stretched to 1,300 cc, but the performance people wanted more, so a new, larger V4 (with a slightly different angle between the cylinders) was designed, the 1600. This engine in the Coupe HF became the serious hot setup. The factory racing “Variante 1016” version made 132 horsepower vs. 100 horsepower for the HF 1300, which was a serious power boost for an 1,850-pound car.

The 1600 HF was a serious rally car, instantly recognizable by its fender flares and the large-headlight “fanalone” front design — along with Plexiglas windows, no bumpers, and aluminum body parts, all to save weight. I’ve never driven one, but I’m told that they are a hoot to drive, and they were extraordinarily successful both in rallying and on the track, with class wins and high overall finishes at venues such as Sebring, Daytona and the Targa Florio.

Lancia scored more international rally championships than any manufacturer in that era and maybe ever.

Great cars — but too many of them

Fabulous little things that they were, the Fulvias have never been collectible cars. A basic problem is that Lancia built 124,000 Fulvia coupes, so retrofitting a stock coupe to look like a 1.6 HFS is a simple enough matter. Having a “real one” is plenty cool, but you’ll have to explain it a lot, which kills collectibility. Even the best ones are valued as weapons-grade cars, and their worth lies in how much fun you can have with them. This is not insignificant, particularly in Europe, where vintage rallying is easily as popular as vintage track racing, but they have to be valued as toys — not keepsakes.

The best value comparison for Fulvias seems to be the race-prepared 1275 Mini Cooper S. The best examples of both Minis and Fulvias with certified history might occasionally break $100,000, but average “Let’s go racing” cars float between $65,000 to $85,000. Our subject Fulvia sold at the low end of the range, about in line with other auction Fulvia HFs and a bit below private sales. I would conclude that the price was market-correct and that this Lancia was fairly bought and sold. ?

(Introductory description courtesy of Bonhams.)