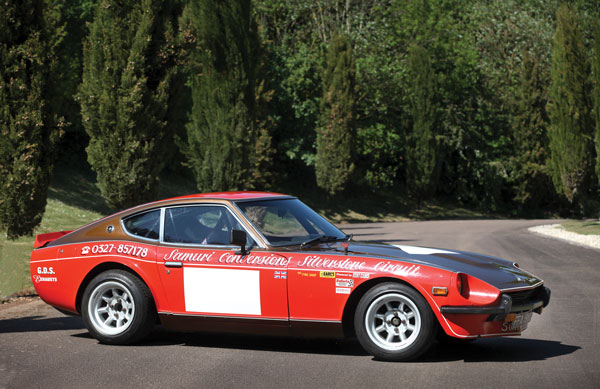

Among U.K. Datsun enthusiasts, particularly those with a fondness for the 6-cylinder Z series, there is no bigger name than that of Spike Anderson, legendary proprietor of Samuri Conversions and the man responsible for a succession of Z-based racers in the 1970s, most notably Win Percy’s famous “Big Sam.” Very few cars are so famous that they are commonly referred to by their registration number, but FFA196L is one such and rightly so, as it was the first Datsun 240Z to benefit from Spike’s attention, going on to become a motorsport legend. This was the first car to carry the ‘Samuri’ name, a deliberate misspelling, as the Samurai trade name was owned by another company.

In 1973, Spike purchased a Datsun 240Z registered FFAl96L for his personal transport, but the car did not remain standard for very long. What would turn out to be a lengthy and ongoing program of tuning commenced with gas-flowing the 2.4-liter, overhead-camshaft six’s cylinder head and raising the compression ratio, which was followed by ditching the standard carburetors in favor of triple Weber 4ODCOEs. Mangolesti supplied special inlet and exhaust manifolds, and in this specification, maximum power increased from 150 to 190 horsepower.

Suspension improvements consisted of lowering the car by 40 mm and replacing the standard shock absorbers with Koni items. The weak braking was addressed by using ventilated discs and four-pot calipers from a Range Rover. Fitted with a deep front spoiler and refinished in distinctive red/bronze livery, Spike’s “Super Samuri” soon gained the attention of the motoring press. Various magazines tested the car and gave it rave reviews, typically achieving performance figures of 0–60 mph in 6.4 seconds and a top speed of 140 mph.

FFA196L was pressed into service as the company demonstrator, and it was also used in competitions, contesting the 1973 British Hillclimb Championship. Despite competing against purpose-built lightweights, the Super Samuri finished 2nd in class at the season’s end, hinting at the 240Z’s potential. Keen to exploit it to the full, Spike acquired an ex-Works 240Z rally car, which he converted to full race specification. Christened “Big Sam” and driven by Win Percy, this legendary car went on to achieve considerable success. Scheduled to race in the 1974 Modsports Championship, “Big Sam” encountered problems on its Silverstone debut, forcing the team to fall back on “Super Samuri.” The car continued to serve as backup for “Big Sam” throughout the 1974 racing season, competing on no fewer than twelve occasions. Always driven to and from the meetings, it also doubled as a customer and press demonstrator, development hack and Spike’s own transport, covering 35,000 miles by the end of the year.

“Super Samuri” competed in 14 Modsports races in 1978, finishing 2nd in class at the season’s end, a feat repeated in 1979, ‘80 and ‘81. Spike appears to have had an off year in 1982, as the 240Z could only manage 3rd. By now FFA196L had been driven more than 175,000 miles, competed in more than 60 races and 20 hillclimbs, and was featured in 15 magazine articles, making it arguably the best-known Japanese car in the U.K.

SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Number Produced: | 150,000 |

| Original List Price: | about $4,500 U.S. ($6,600 in the U.K.) |

| Chassis Number Location: | Stamped on firewall |

| Engine Number Location: | Boss on side of block |

| Club Info: | Classic Zcar Club |

| Website: | http://www.classiczcars.com |

This car, Lot 428, sold for $90,450, including buyer’s premium, at the Bonhams Goodwood Festival of Speed auction on July 1, 2011.

I’ve often held forth on the idea that the value of an old racing car is a function of some combination of dynamic “How much fun can I have using it?” values and static “How much money would the next guy part with simply to own it?” values. In other words, weapons values and collector values.

Weapons values are both limited by competitive factors (if I can be as fast and have as much fun in a Mustang, why pay more to run a Jaguar) and limited at some absolute amount (I propose about $200,000; to be worth more than that, a car has to have some enduring collector value).

Collector values are self-evident: beauty, exclusivity, history, exotic and expensive construction, celebrity, and so on. These values are unlimited. The greatest cars tick all the boxes on both sides — they’re great weapons and great collectors.

The “Super Samuri” poses this question: “Can a common-as-dirt production car that was built into a regional racer by a privateer using off-the-shelf parts — and that is fundamentally not usable as a vintage racer — have substantial value, and if so, why?” The answer clearly is yes; understanding why is the interesting part.

A common, inexpensive sports car that worked

On the surface, a 240Z is not a promising place to start looking for a collectible car. Nissan built about 150,000 of them over a four-year period, and they were sold as an inexpensive alternative to Jaguars, Porsches and Corvettes. They had a steel body, vinyl interior and a mechanical package about as exotic as a washing machine. In spite of all that (possibly because of it), the cars worked amazingly well. They were refreshingly quick and light on their feet, had a great exhaust note, and mostly they just plain worked: Lights lit, heaters heated, wipers wiped and the engines ran, all without drama or insecurity.

Forty years after the fact, it’s easy for us to forget just how poorly built most cars were in the early 1970s, particularly in England. A combination of rapidly changing regulations, labor troubles, economic malaise and general mismanagement conspired to produce some of the clumsiest, worst-built cars in the history of the automobile. (An associate of mine recalls that the workshop manual for a Lotus of that era opened with the statement, “A certain amount of ambient failure is to be expected.”)

Into this gaping breach charged the Japanese, with Nissan in the lead. They offered a paradigm shift of inexpensive, fun cars that offered quality and performance levels unheard of for the price. We now take it for granted, but modern build quality didn’t just happen — the Japanese forced it. The 240Z may not be collectible, but in many ways it is extremely important in the evolution of the automobile.

Grassroots modifications

Spike Anderson in the ’70s was a racer and performance guy whose specialty was making cylinder heads breathe better. He bought our subject car as his personal street ride and was quickly seduced by the 240Z attributes. Anderson proceeded to form a company, Samuri Conversions, to provide hot-rod modifications of the car in the U.K. It is important to note here that although Nissan produced a few special rally 240Zs for events such as the East Africa rally, they had no general interest in competition. There was no factory team.

A second point is that Spike and his friends had neither the budget nor the inclination to race on the international stage with its rules and restrictions, so the Samuri cars were built to compete in the grassroots “Modsports” races in the U.K. The result is that the Samuri racers have modifications (Webers, Land Rover brakes, 2.8-liter engine blocks) that keep them from being acceptable in most contemporary vintage racing events. Most of the 77 Samuri conversions that Anderson built have thus faded into obscurity or breakers’ yards, as they are just old, hot-rod 240Zs.

One of two famous cars

There were two cars, though, that served as poster children for everything that Anderson and Samuri aspired to: our subject car and “Big Sam,” the serious racer they built out of a factory rally car for Win Percy. These two cars were amazingly successful in their time, becoming giant killers in the English “Modsports” realm by being very quick and absolutely unbreakable. They caught the public’s imagination as the embodiment of the Rising Sun in U.K. racing. Magazine writers couldn’t get enough of them, and people turned out to cheer them on.

Of all the Japanese racers in the U.K. during the late 1970s and early 1980s, these two cars were the ones that became famous. As such, the two cars earned a collectible status that no other 240Z could dream of. A year ago “Big Sam” sold at auction for $119,000. Our subject car sold for about 25% less, but it is the lesser car. I’m told the same purchaser acquired both 240Zs, wanting to keep the cars together.

It is possible for a car of humble beginnings to attain collector value. It requires fame, extraordinary accomplishment and iconic status to get there, but the value is real (and the absolute value is still pretty modest, as it’s no Ferrari 250 GTO). I’d say the car was fairly bought as a collector piece.

(Introductory description courtesy of RM Auctions.)