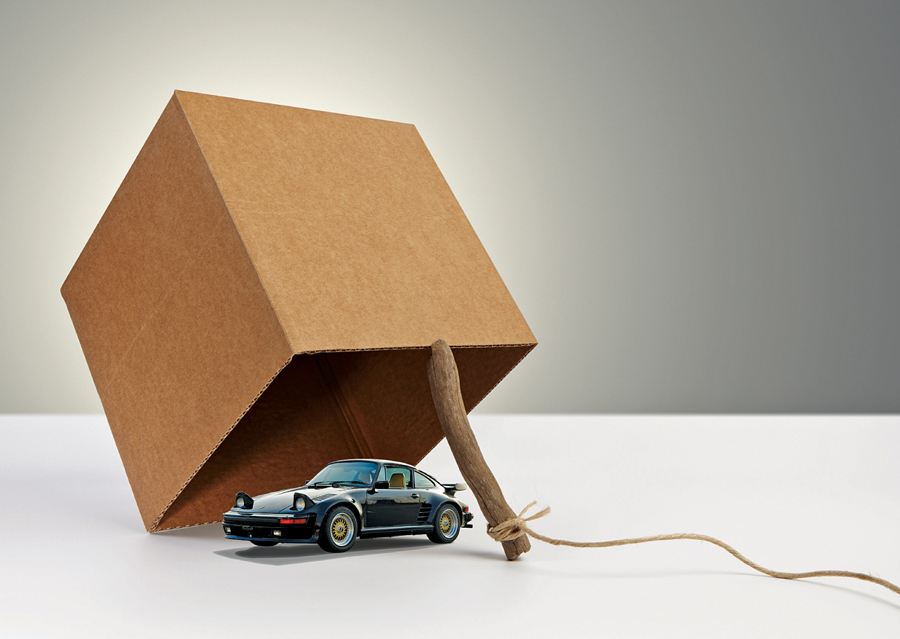

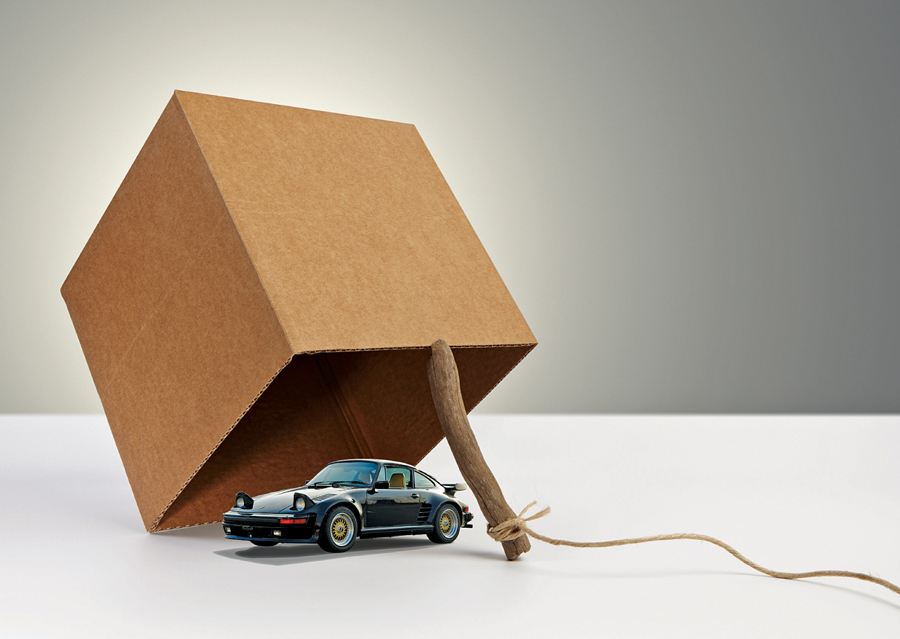

Legal Traps for the Unwary Seller

They say that all good things come to an end — and now it’s time to sell your collector car. While it may seem like an easy thing to do, there are a lot of potential legal land mines waiting for you when you become a collector-car seller. Auctions The first thing to come to…

Your cart is currently empty!

Notifications