No chassis number available

The Porsche 917 K was the direct result of years of intense research. Although it employed the most modern concepts in automotive design, the new car was absolutely in keeping with Porsche tradition. The foundation of the new model was an incredibly lightweight aluminum space-frame chassis. Similarly, the suspension systems made extensive use of lightweight materials such as titanium and magnesium.

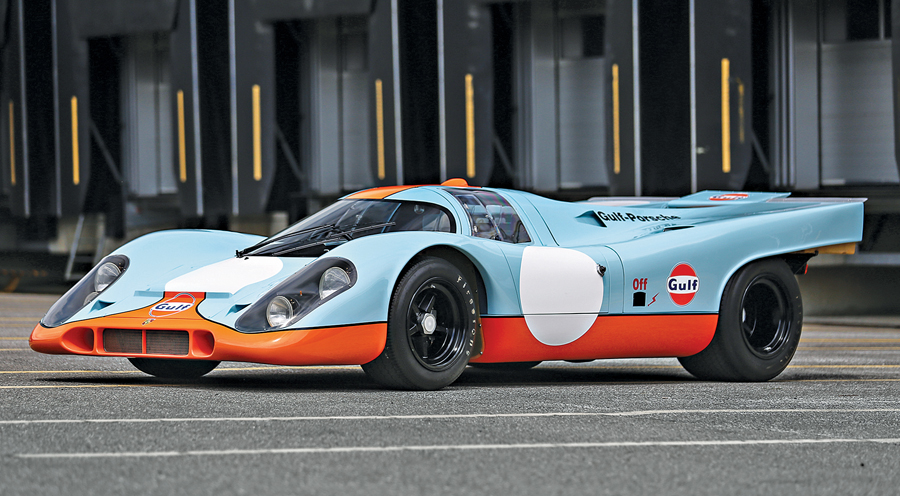

Glued to this frame was a striking, streamlined body made from thin fiberglass. Covered in NACA ducts and suspension-controlled aerodynamic flaps, the shape of the new Porsche was honed in the wind tunnels at the Stuttgart Technical Institute.

This magnificent car’s air-cooled flat 12-cylinder engine is an undisputed masterpiece of automotive engineering designed by the legendary Hans Mezger. With dual overhead camshafts, twin-plug ignition, Bosch mechanical fuel injection, dry-sump lubrication and the distinctive, mechanically driven six-blade fan, it delivered 580 bhp at 8,400 rpm in original 4.5-liter form.