Some companies can lock one label into the consumer’s mind. This is especially true in the auto industry. Volvos are safe, Subarus are sensible, Saabs are odd and Lotuses are lightweights.

Lotus mastermind Colin Chapman’s philosophy seemed to consist of omitting, thinning and paring—until the car collapsed on itself—and then put back the last thing either omitted, thinned or pared and calling it well done. All this made for cars that handled well and extracted the maximum performance out of the smallest and most efficient engines, but if Lotus gets a second label in the hearts and minds of car guys, it would have to be “fragile.”

The economics of the 1970s, which included inflation and currency fluctuations, were not kind to Lotus. The company was forced to compete at unfamiliar price points. When Road & Track tested its first Lotus Elan in the early 1960s, they accepted the fact that during the course of the test, things would come loose or even fall off. After all, Lotus still offered some of its cars in kit form.

That level of tolerance ended with the demise of the Europa. Future Lotus cars would have to be less homemade and more professionally executed.

The Esprit’s mixed bag

The first “real car” Lotus was the dreadful Elite of 1974. While the Elite was the most luxurious Lotus yet offered, its styling was bizarre and the new Lotus 907 twin-cam engine suffered teething troubles in both the Elite and the Jensen-Healey. Workmanship was no better than any previous Lotus product.

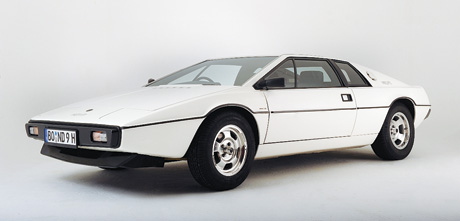

The real replacement for the Europa came in the upmarket Esprit. First shown at the Turin Motor Show in 1972, it was a tour de force styling effort by Giorgetto Giugiaro and probably the best expression of the wedge theme popular in the 1970s. Underneath, it was typical Lotus. The color-impregnated fiberglass body clothed a backbone frame and mid-engine architecture similar to the late Europa.

And, like no Lotus since the 1950s Elite, the Esprit looked smashing. The first 1976 press cars all seemed to be yellow with polished, slotted Wolfrace alloy wheels and plaid cloth seat inserts reminiscent of Jackie Stewart’s helmet. I remember wanting one in the worst way.

Sadly, in the worst way is precisely how the early Esprits were delivered to their eager owners. Quality control was dismal. U.S.-spec cars were particularly disappointing from a performance standpoint, with the 507 engine forced to inhale through Zenith-Stromberg 175 carbs instead of the Dell’Orto units that the rest of the world got.

The car’s 0-60 mph times were around eight seconds, with a top speed of around 130 mph. It actually compared favorably with the much larger Maserati Merak, Ferrari Dino 308 GT/4 and Lamborghini Urraco.

James Bond’s ride

Still, well-heeled enthusiasts everywhere clamored for the car, particularly after it made the highest profile car appearance in a Bond film since the Goldfinger Aston Martin DB5. In 1978’s “The Spy Who Loved Me,” Roger Moore’s white Esprit doubled as a submarine—and an immensely popular Corgi car.

Series 2 cars from 1978-81 added a front air dam, cooling ducts behind the rear quarter windows, bespoke alloy wheels and Rover SD-1 taillights to replace the Fiat X1/9 sourced units.

Some began to grumble that the purity of the original Giugiaro design was being lost. The last of the normally aspirated Series 2 cars of 1981 had a 2.2-liter 907 engine known as the 912. From there on, the cars became more complex with the introduction of the turbocharged Essex Esprits. The final incarnation of the original Giugiaro Esprit came in 1986 and added Bosch fuel injection for the first time.

Not an A-list car

Esprits are sort of junior exotics in both execution and potential costs of running. They’re not potentially ruinous like a Ferrari, but all except the best examples can be a genuine pain in the backside.

Steel frames can and do rust, fiberglass can exhibit stress cracks and Renault-sourced gearboxes can be troublesome. The 907 engine is a perennial leaker from the cam covers, which leads to the noxious smell of burning oil in the cabin. Thankfully, Dave Bean Engineering has the fix for this—and the timing belt tensioner problem.

In terms of collectible value, few Lotuses beyond the original Elite and race cars such as the Eleven have cracked the A-list. Series 1 and 2 Esprits are unlikely to do so. However, there has been some recent interest in the few really good examples out there. If you must have a legitimate Bond car, a white Lotus Esprit S1 is the cheapest route. It’s unlikely that you’ll lose any money on a great example.