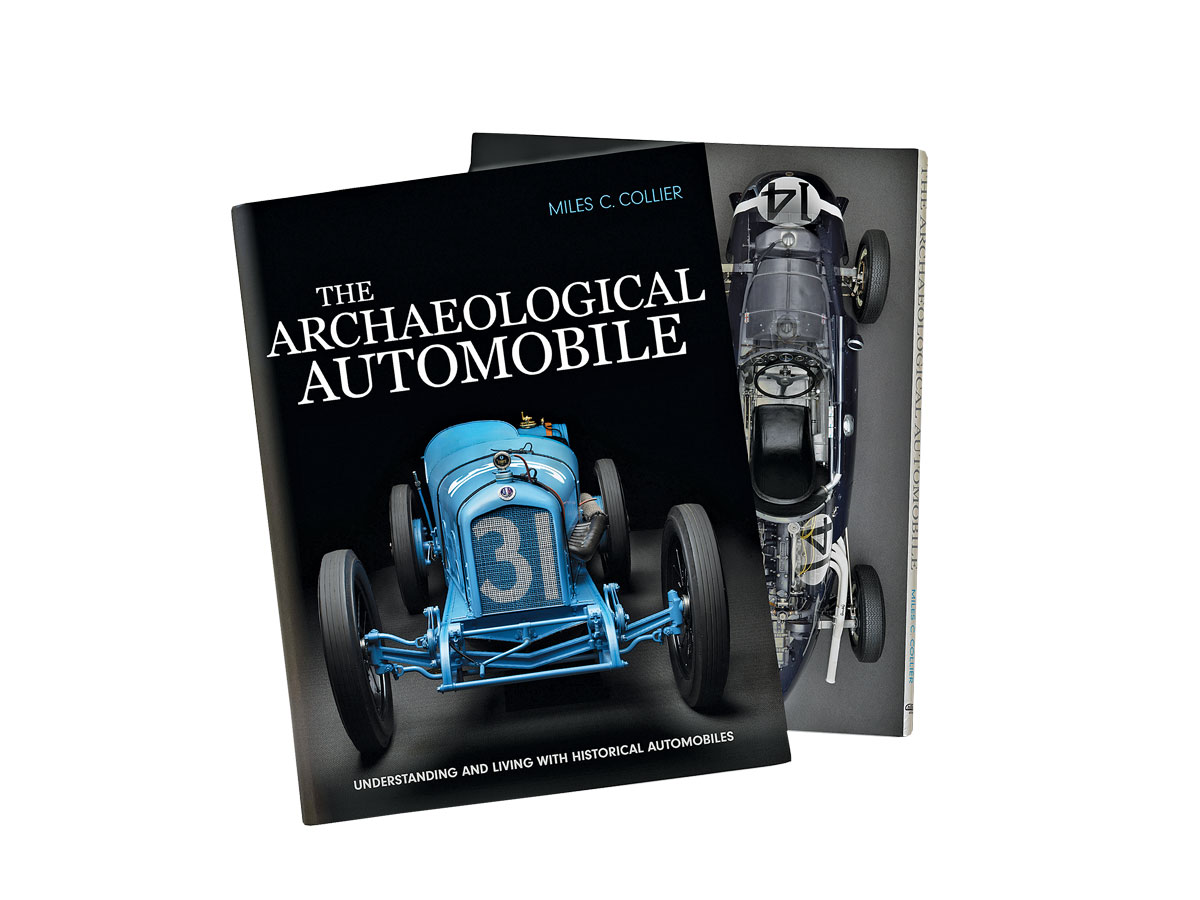

“That’s a really valuable collector automobile.” Or, “This car will be a very important addition to a collection.” What do we really mean when we make such judgments? Whenever we go to shows, auctions, tours, and races, we hear these remarks. But have you ever wondered what goes into making a car important or valuable,…

What Makes an Automobile Collectible?