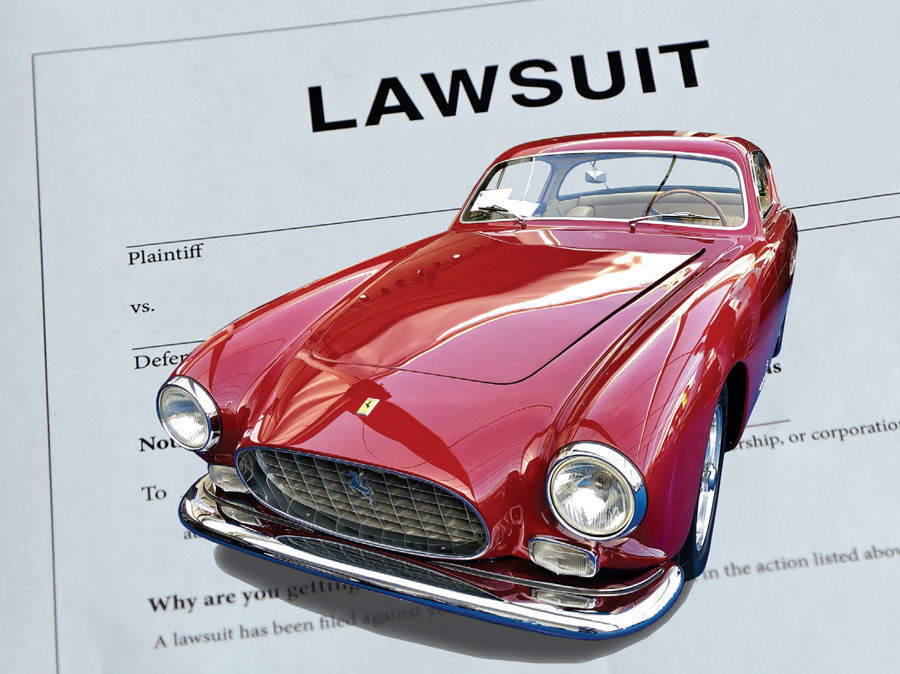

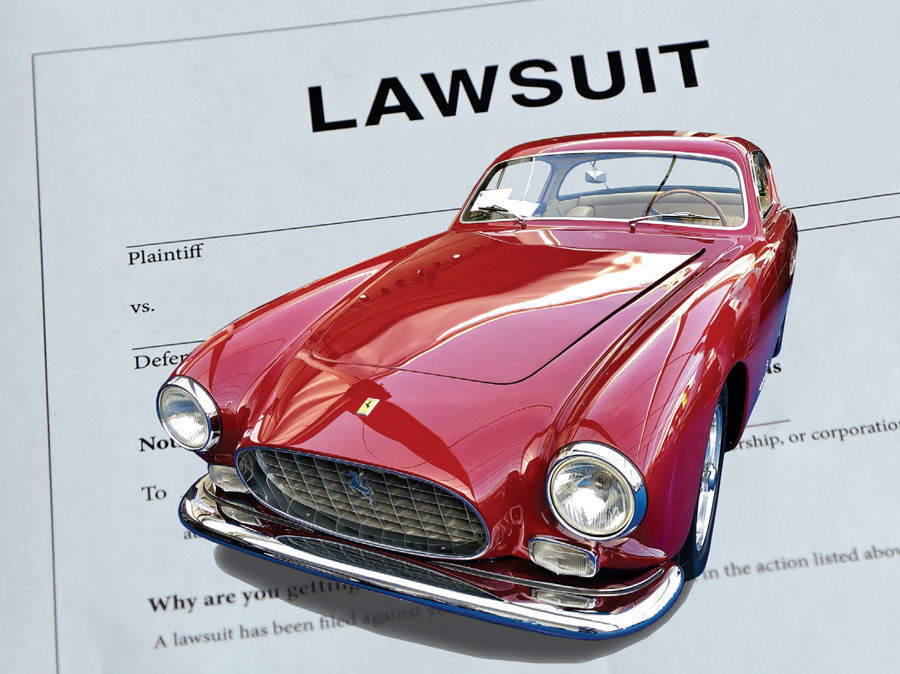

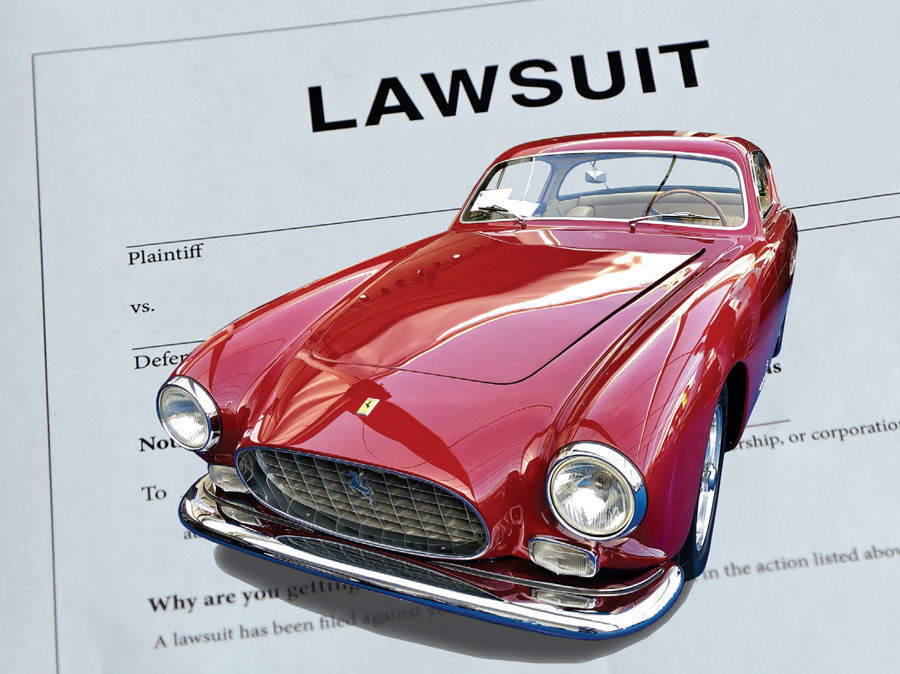

Falcon Woods LLC, a Nevis, West Indies, limited-liability company, was about to cut a fat hog. It had consigned its 1954 Ferrari 250 Europa GT coupe, chassis number 0379GT, to Gooding & Company for its 2018 Scottsdale auction. The estimated sales price for Lot 116 was $1.6m to $2m. Just before the auction started, Falcon Woods received an alarming phone call. Gooding had been contacted by a Peter Piper, who claimed that the Ferrari still belonged to the estate of his deceased father, James Piper.

Even worse, Piper and/or his attorney had threatened to disrupt the auction by announcing that the Ferrari had been stolen. Gooding recommended that the Ferrari be pulled from the auction.

Falcon Woods wondered how that could be. They had purchased the car off a Louisiana title issued to V-Twelve Ltd., and had a clean chain of title from there.

Even though the Europa GT was pulled from the auction, Piper filed suit against Gooding and several “John Does,” asking the court to enjoin the sale of the Ferrari and to order Gooding to hold onto it until this was all sorted out. The court issued that order, and Gooding placed the car in storage pending resolution of the claims. Piper’s main goal was to find out who the “owner” of the Ferrari really was.

A tangled web

James Piper had purchased the Europa GT in 1962. In 1989, after reputedly having declined an offer of $1.7m for the car, he moved to Mexico. He soon became romantically involved with Maria Socorro De Rodriguez La Pine, who had become known to the FBI as the “Black Widow of Guadalajara.” Socorro had been implicated in at least eight murders, suspected of murdering prior love interests and dispossessing them of their assets. Piper believed that his father had become one of her victims.

The transfer of ownership of the Ferrari gets real murky here. According to Falcon Woods, James Piper transferred the Ferrari by bill of sale on September 12, 1989, one week before his death, to V-Twelve Ltd., and a Louisiana certificate of title was issued to V-Twelve on October 6, 1989.

Socorro, acting on behalf of V-Twelve under a power of attorney, sold the car to Robert Butler for $300,000. In 1991, Butler sold the Ferrari to Todd Morici for $150,000. Morici then sold the car to Falcon Woods’ predecessor entity.

Piper tells a different story. Socorro told him that his father wanted to transfer this and his other Ferraris to V-Twelve for the benefit of his children and had retained a New Orleans attorney to do that for him.

She invited Piper to travel to New Orleans with her to see the attorney, which he did. They met with him after James had died. The New Orleans attorney stated that he had started on the transfers but stopped work when he learned that James had died and did not want to proceed with the transfers unless Piper approved. Piper indicated his approval but never received any of the paperwork that he expected if the transfers were to proceed.

But either way, the car had not been transferred before James died and could not be transferred afterward without the action of the executor of the estate. It was after that meeting that Socorro used her power of attorney to transfer the Ferrari to Butler.

Who to sue?

When Piper learned the Europa GT was included in the Scottsdale auction, he traveled to Scottsdale, determined that this was his father’s car, and presented Gooding’s in-house counsel with his claim. He then filed suit against Gooding.

It made perfectly good sense for Piper to sue Gooding — they had the car, they were going to sell it and he had no idea who the owner was. After it became known that Falcon Woods was the owner, Gooding filed a motion to be dismissed from the lawsuit. Piper successfully resisted the dismissal. Evidently, Gooding was stuck because they still had the car.

Certificate of title inconclusive

The case recently came up for summary judgment. Piper and Falcon Woods had both filed motions asking to be declared the winner without need for a trial because the law was clearly in their favor. Gooding just asked to be allowed to go home.

To win on summary judgment, a party must establish that there are no questions of fact — that is, there are no disputes about what happened and what the situation is. Plus, it must show that it is entitled to prevail under the law.

Falcon Woods asserted that the New Orleans certificate of title established that V-Twelve owned the Ferrari, and the transfers that resulted in its ownership were conclusive.

The court disagreed, pointing out that a state’s certificate of title was not conclusive, but only evidence of ownership. Ownership could be rebutted by contrary evidence, and Piper had lots of that. It would take an actual trial to determine if Piper’s evidence was enough to establish his father’s continued ownership.

By the same token, Piper was not entitled to a declared victory because it was not clear that his evidence would be enough. He needed to win at trial to establish his father’s ownership.

No innocent purchaser

Falcon Woods made a second argument — it was the innocent purchaser of the Ferrari, and California law gave it ownership for that reason.

This was a more interesting argument, but the court pointed out that, under California’s innocent-purchaser statute, you have to distinguish between a car that was taken by fraud and one taken by theft. If the car was taken by theft, the innocent-purchaser defense does not work. A thief has no title and cannot pass title to another. But if V-Twelve obtained title by fraud, Falcon Woods could be an innocent purchaser.

But to be an innocent purchaser, one must be a bona fide purchaser for value. Here, Falcon Woods seemed to have purchased the Ferrari for much less than its market value. If that was the case, then it would not be a bona fide purchaser under the law, and the innocent-purchaser defense would not apply.

What about Gooding?

Gooding was just collateral damage in this ownership dispute between Piper and Falcon Woods. Once Falcon Woods was identified as the owner, there was really no reason for Gooding to still be involved. The court dismissed them from the case.

An auction company is really nothing more than a broker. It is not the seller. Rather, it sells the car as an agent for the owner. If there are problems with the car, you almost always have to sue the seller, not the auction company.

What’s next?

In two words, more litigation. All either side accomplished was that it didn’t lose. They both get to fight another day and they both have huge proof problems.

Falcon Woods has no direct access to the 1989 facts, and a below-market purchase does not put it in a good light. I have no idea who the owners of Falcon Woods are, and if they end up being connected to the participants in the 1989 drama, there may be a backlash.

Meanwhile, Piper must come forward with some pretty good evidence to win the case. It’s easy to insinuate that the “Black Widow of Guadalajara” killed his father, but proving it is another matter since his father’s body was cremated and the cause of death is unknown.

There has also been no indication that the New Orleans lawyer is around. If he is not available to testify, it may be hard to establish just what did happen in 1989.

A word to the wise

This is definitely not good news for car collectors, but this case points out the limitations of a certificate of title: It is not absolute proof of ownership.

Many of today’s valuable cars were essentially junk at one time, and ownership records may have been sketchy at some time. In a large transaction where you don’t know the seller and the ownership history of the car, it makes good sense to investigate the chain of ownership thoroughly. Don’t just assume that the certificate of title establishes absolute legal ownership. It may not. ♦

John Draneas is an attorney in Oregon. He can be reached through

www.draneaslaw.com. His comments are general in nature and are not intended to substitute for consultation with an attorney.

Falcon Woods LLC, a Nevis, West Indies, limited-liability company, was about to cut a fat hog. It had consigned its 1954 Ferrari 250 Europa GT coupe, chassis number 0379GT, to Gooding & Company for its 2018 Scottsdale auction. The estimated sales price for Lot 116 was $1.6m to $2m. Just before the auction started, Falcon Woods received an alarming phone call. Gooding had been contacted by a Peter Piper, who claimed that the Ferrari still belonged to the estate of his deceased father, James Piper.

Even worse, Piper and/or his attorney had threatened to disrupt the auction by announcing that the Ferrari had been stolen. Gooding recommended that the Ferrari be pulled from the auction.

Falcon Woods wondered how that could be. They had purchased the car off a Louisiana title issued to V-Twelve Ltd., and had a clean chain of title from there.

Even though the Europa GT was pulled from the auction, Piper filed suit against Gooding and several “John Does,” asking the court to enjoin the sale of the Ferrari and to order Gooding to hold onto it until this was all sorted out. The court issued that order, and Gooding placed the car in storage pending resolution of the claims. Piper’s main goal was to find out who the “owner” of the Ferrari really was.

Falcon Woods LLC, a Nevis, West Indies, limited-liability company, was about to cut a fat hog. It had consigned its 1954 Ferrari 250 Europa GT coupe, chassis number 0379GT, to Gooding & Company for its 2018 Scottsdale auction. The estimated sales price for Lot 116 was $1.6m to $2m. Just before the auction started, Falcon Woods received an alarming phone call. Gooding had been contacted by a Peter Piper, who claimed that the Ferrari still belonged to the estate of his deceased father, James Piper.

Even worse, Piper and/or his attorney had threatened to disrupt the auction by announcing that the Ferrari had been stolen. Gooding recommended that the Ferrari be pulled from the auction.

Falcon Woods wondered how that could be. They had purchased the car off a Louisiana title issued to V-Twelve Ltd., and had a clean chain of title from there.

Even though the Europa GT was pulled from the auction, Piper filed suit against Gooding and several “John Does,” asking the court to enjoin the sale of the Ferrari and to order Gooding to hold onto it until this was all sorted out. The court issued that order, and Gooding placed the car in storage pending resolution of the claims. Piper’s main goal was to find out who the “owner” of the Ferrari really was.

Falcon Woods LLC, a Nevis, West Indies, limited-liability company, was about to cut a fat hog. It had consigned its 1954 Ferrari 250 Europa GT coupe, chassis number 0379GT, to Gooding & Company for its 2018 Scottsdale auction. The estimated sales price for Lot 116 was $1.6m to $2m. Just before the auction started, Falcon Woods received an alarming phone call. Gooding had been contacted by a Peter Piper, who claimed that the Ferrari still belonged to the estate of his deceased father, James Piper.

Even worse, Piper and/or his attorney had threatened to disrupt the auction by announcing that the Ferrari had been stolen. Gooding recommended that the Ferrari be pulled from the auction.

Falcon Woods wondered how that could be. They had purchased the car off a Louisiana title issued to V-Twelve Ltd., and had a clean chain of title from there.

Even though the Europa GT was pulled from the auction, Piper filed suit against Gooding and several “John Does,” asking the court to enjoin the sale of the Ferrari and to order Gooding to hold onto it until this was all sorted out. The court issued that order, and Gooding placed the car in storage pending resolution of the claims. Piper’s main goal was to find out who the “owner” of the Ferrari really was.

Falcon Woods LLC, a Nevis, West Indies, limited-liability company, was about to cut a fat hog. It had consigned its 1954 Ferrari 250 Europa GT coupe, chassis number 0379GT, to Gooding & Company for its 2018 Scottsdale auction. The estimated sales price for Lot 116 was $1.6m to $2m. Just before the auction started, Falcon Woods received an alarming phone call. Gooding had been contacted by a Peter Piper, who claimed that the Ferrari still belonged to the estate of his deceased father, James Piper.

Even worse, Piper and/or his attorney had threatened to disrupt the auction by announcing that the Ferrari had been stolen. Gooding recommended that the Ferrari be pulled from the auction.

Falcon Woods wondered how that could be. They had purchased the car off a Louisiana title issued to V-Twelve Ltd., and had a clean chain of title from there.

Even though the Europa GT was pulled from the auction, Piper filed suit against Gooding and several “John Does,” asking the court to enjoin the sale of the Ferrari and to order Gooding to hold onto it until this was all sorted out. The court issued that order, and Gooding placed the car in storage pending resolution of the claims. Piper’s main goal was to find out who the “owner” of the Ferrari really was.