My interest was immediately aroused when I saw this in my inbox, a letter on which I had been cc’ed, from a renowned Ferrari expert and historian: Attn. Mr. Rod Egan, Worldwide Auctioneers: I have been reading the January 2021 issue of Sports Car Market magazine and saw the Worldwide ad for the Arizona auction,…

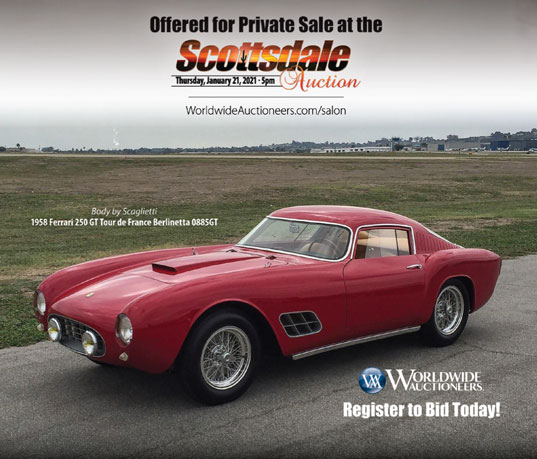

Is This a Ferrari TdF — or Something Else?