The Republican Party’s Christmas present to all of us was a new tax law. It made good on several promises, the most notable being President Trump’s promise to get it done before Christmas. Ballyhooed as the most significant tax reform measure since 1986 — that it definitely is, although reasonable minds can differ about whether…

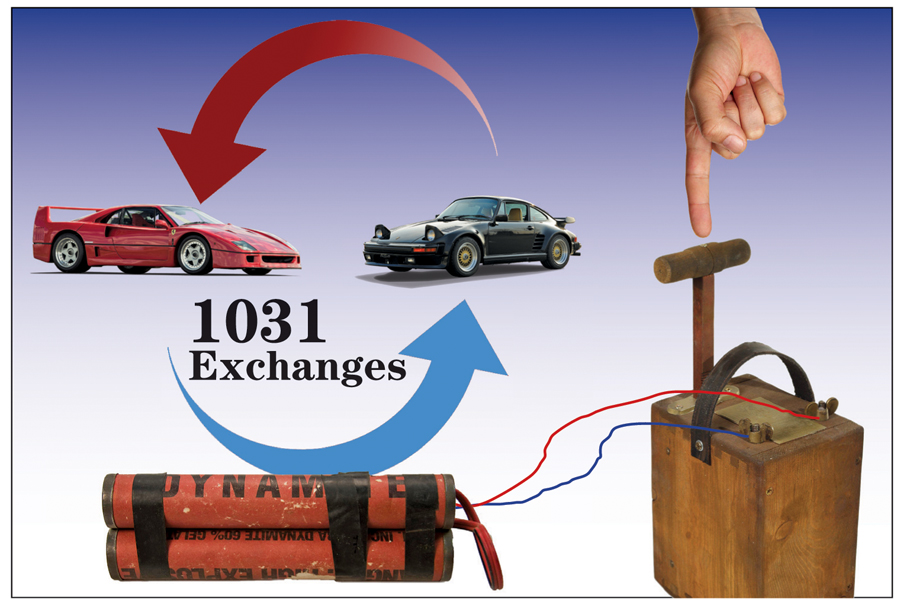

The New Tax Landscape for Collectors