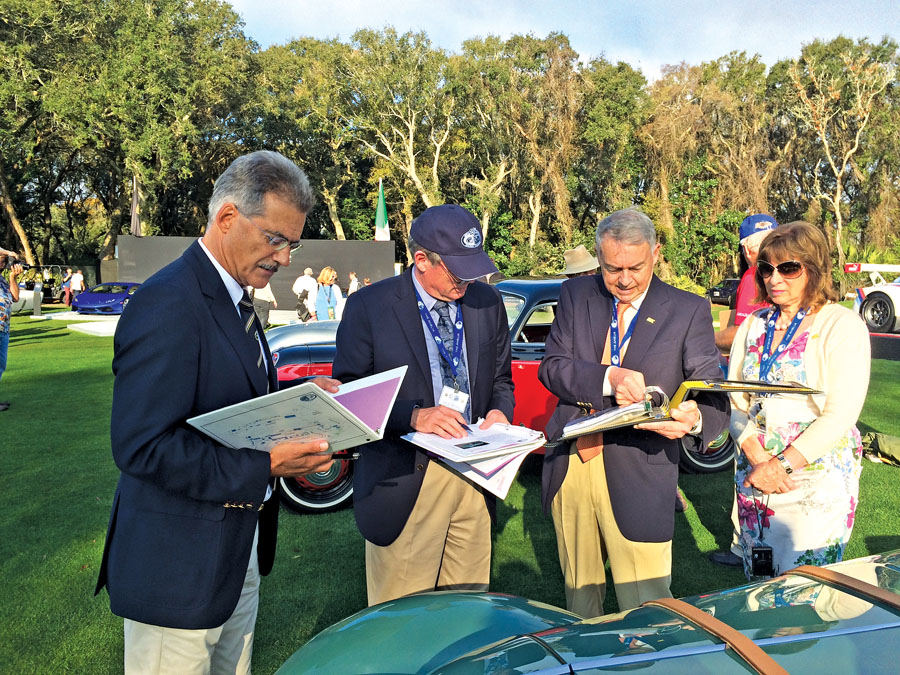

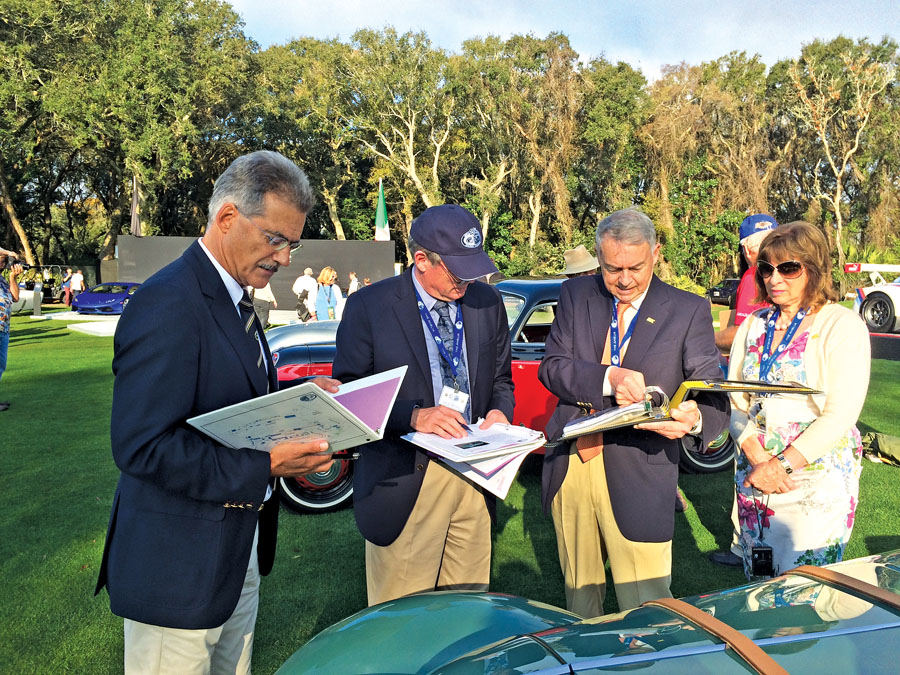

Here Comes the Judge

What do a 1968 Ford GT40 Mk III, a 1967 Porsche 911S, a 1972 4.9 Ghibli Spider SS, a Toyota 2000GT, a 1972 Ferrari 246 GT and a 1968 DeTomaso Mangusta prototype have in common? These are exotics with 6- and 8-cylinder engines placed in the front, middle and rear of their chassis. The GT40…

Your cart is currently empty!

Notifications