Two years ago, the art market had cratered, with both Sotheby’s and Christie’s suffering huge year-over-year declines in their annual New York sales.But on February 3, the market spoke with an authoritative voice, as “Walking Man I,” a life-size bronze sculpture by Alberto Giacometti, was sold by Sotheby’s for $104.3m, a world record for the…

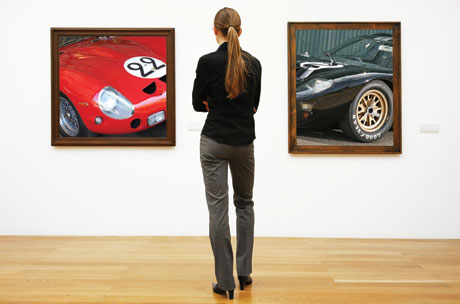

The Market Walks Tall