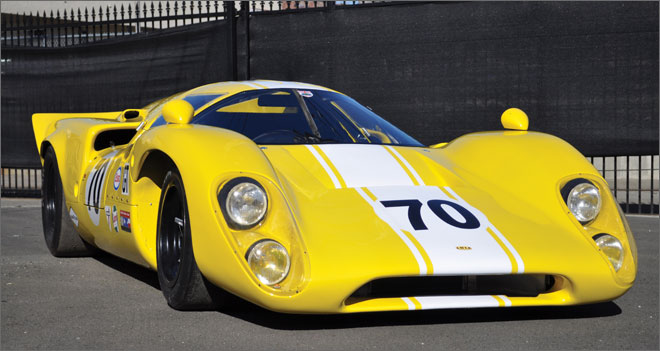

Eric Broadley’s Lola project, the legendary T70, debuted in 1965 and quickly demonstrated its prowess in the hands of John Surtees, who won the inaugural Can-Am Championship in 1966. The T70 was produced in open Mk II Spyder and Mk III Coupe forms until 1968. Although eclipsed by the Ferrari 512 and Porsche 917, the race-proven Lola T70 demonstrated its reliability and speed when Mark Donohue and Chuck Parsons won the 1969 24 Hours of Daytona in a Roger Penske-entered, Chevrolet-powered Mk IIIB Coupe. The T70 was driven by a veritable “who’s who” of 1960s motor racing stars on both sides of the Atlantic.

Documenting the history of racing cars can frequently prove to be a difficult task. Many are subject to hard use, crashes, modifications, or uprating, which only makes the task of substantiating provenance more challenging. Although it cannot be documented conclusively, chassis 73-135, the car offered here, may very well be one of about five Mk III road cars built up with tubular space frames by famed car designer Franco Sbarro from parts and components he acquired.

There is also a possibility that it may even be one of the 16 original T70 Mk III GT coupes originally built by Lola, but it should be noted that the chassis number does not correspond with any known examples. Still others believe that this was the car used and crashed in the making of the Steve McQueen film “Le Mans” and subsequently rebuilt in France.

Fresh from a three-year, no-expense-spared professional restoration and finished in bright yellow with a polished aluminum tub, it features a mid-mounted 355-ci Chevrolet engine that produces about 600 horsepower. Equipped with a correct Hewland gearbox, Vertex magneto, proper Lola brakes, Lola uprights and authentic period gauges, it also has the correct 15-inch Lola wheels shod with new racing slicks. Impressively restored, this car is ideally suited for various historic track events around the country.

SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1968 Lola T70 Mk III GT Coupe |

| Years Produced: | 1967-1969 |

| Number Produced: | 30 coupes |

| Original List Price: | unknown |

| SCM Valuation: | Bitsa: $150,000-$200,000, Authenticated: $850,000-$1,250,000 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Tag on tub in engine bay |

| Engine Number Location: | On block at right front |

| Club Info: | Lola Cars Club International |

| Website: | http://lolacarsclub.com |

| Alternatives: | 1964-69 Ford GT40, 1969 McLaren M6 coupe, 1964-65 Ferrari 250LM |

This car, Lot 137, sold for $165,000, including buyer’s premium, at RM Auctions’ Amelia Island auction on March 12, 2011.

You could argue that this whole thing started when Enzo Ferrari told Henry Ford to get lost when he wanted to buy the Italian marque. Eric Broadley was struggling along while building small-bore racing cars under the Lola banner, but he could see that the advancing technology in chassis, transaxle, and tire design was making a mid-engined racer that utilized American V8 power in a monocoque chassis designed for the new, wider tires that were becoming available a viable possibility.

At the Olympia (London) Racing Car Show in January 1963, Lola introduced their Lola Mk 6 GT (profiled in SCM, December 2006), which, although cobbled together and barely operational, caught the racing world’s imagination. It was a stunningly beautiful little coupe that used a Ford V8 and it happened along just at the moment when Ford was looking for an English race car manufacturer to buy in order to go beat Ferrari.

Lola looked to be just the ticket, and by mid-1963, Ford had bought Lola (renamed Ford Advanced Vehicles) and embarked on what was to become the GT40. However, Broadley’s honeymoon was very short. Disagreements quickly erupted, particularly over Ford’s insistence that the new car’s chassis monocoque be constructed of steel, which was absolute anathema to a committed racing car constructor like Broadley.

Ford’s intent was reasonable, as they wanted to produce a car useable on the street instead of a pure racer, but the incompatibility was apparent. The result was that within a year Ford and Lola had split the sheets in an amicable arrangement, and Broadley had gone back to producing pure racers under the Lola name.

An immediate winner

Unsurprisingly, after dabbling with a few single-seaters, the first two-seater the reconstituted Lola chose to produce was the car Broadley thought Ford should have let him build. The car was an evolution of the Mk 6 and GT40 designs, but with an aluminum monocoque chassis, and pure racing intentions. The new T70 Lola was introduced in January 1965. In deference to his friends at Ford it was not designed to compete in the world championship GT arena, but it was instead a spyder aimed at the burgeoning American—and U.K.—market for no-holds-barred, V8-powered sports racers (FIA Group 7).

The T70 Spyder was immediately successful, with a strong showing in the 1965 USRRC series followed by winning the First Can-Am Championship in 1966. For the 1967 season, the time seemed right to expand the concept and introduce a sports-prototype coupe version of the T70 for European endurance racing. The now-iconic T70 Coupe made its debut.

It is useful to note that Ford, Ferrari, and Porsche—the dominant championship contenders of this period— were racing factory teams for corporate and national glory. In contrast, Lola was a manufacturer in the business of selling racing cars to privateers. That is one reason why T70s tended to fill out the grids and the finishing order at the big races—not dominate them. My count shows 30 T70 coupes originally built out of roughly 104 total T70s, so they were never really common.

Gorgeous, glorious weapons

Although they weren’t the dominant race cars of their era, T70 coupes are absolutely gorgeous things, very user-friendly to race and with their share of historic glory. All of this has endeared them to a generation of vintage car racers. This has given them substantial value as weapons-grade racers, and more recently, has allowed the best of them to make the transition to seriously collectible status.

However, there is a collectibility issue.

Because these cars were constructed in a workshop out of fabricated or subcontracted parts rather than in a manufacturer’s factory with internal casting, machining, and forging capacity—such as Ford, Ferrari and Porsche—Lola T70s have proven very easy to replicate. I don’t think anyone knows how many replicas are zooming around, but there are a lot more T70 coupes out there than ever left the Lola workshop in Slough, England. As is evident in the catalog description above, the subject car may or may not have any claim to being an original Lola, but it was effectively presented and sold as a replica.

No pretense to fame, no foul

There has been a substantial change in attitudes toward the use of non-original cars in vintage racing over the past few years. Whether it is for better or worse fills endless late-night conversations in our world, but the end result is that there are certain categories of cars that are no longer expected to prove their provenance to gain entry in most events (the “big” events are still very careful). For international events, the FIA no longer attempts to address whether a racing car is “real” and only certifies that it meets the technical standards required to participate, while the subjective side is left to the race promoter.

The situation is similar in the U.S., with few organizers asking questions if a car is correct and well-presented. It seems to me that the line in the sand for acceptability has to do with a replica not pretending to be a famous car. Ferrari GTOs and Corvette Grand Sports, for example, are considered so important that a fake one is an insult at an event, while more recent Lolas, Chevrons, Lotus and the like are sufficiently generic that nobody notices or seems to care.

The world’s best Lola T70 Mk IIIB coupes, dripping race history and with unquestioned provenance, bring well over a million dollars these days, while our subject car sold for less than a fifth of that.

Both cars will give a driver a very similar driving experience and lap times, and at 80% of the racing events in the world will be equally acceptable (not equally revered, but welcome to participate).

This gives us an excellent opportunity to look at what creates value. I have long contended that the maximum “weapons grade” value for any vintage racing car in the U.S. is about $200,000. To go above that, you need to look to collector factors. This sale supports my observation. If this car had any collector values, the market chose not to include them in the price. In the case of this car, the cost of the parts alone probably exceeded the final bid, but that is frequently the fate of weapons in a collector’s auction world. As a useable racer, I’d say this car was very well bought.