In the late 1970s, BMW was still in its growing pains in the United States. The favored quirky rally car of the 1960s was becoming the favored fast luxury transport of young professionals.

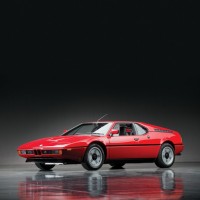

Between the two eras of Bayerische Motoren Werke, there was the M1, which remains the most exotic street car that the company ever built. It was essentially a road-going Procar and Group 5 racer, built to homologize the cars for the track.

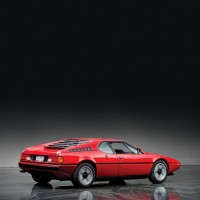

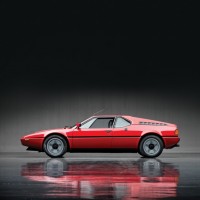

Hand-built in limited numbers, it combined a tubular frame, utilizing state-of-the-art technology with gorgeous Giugiaro-designed wedge bodywork. The chassis was fitted with unequal-length lateral links, alloy uprights, concentric coil springs and anti-roll bars in the front and rear. The mid-mounted, fuel-injected, 277-horsepower, double-overhead-cam 6-cylinder engine reached top speeds in excess of 160 mph, thanks to the M1’s outstanding power-to-weight ratio. Such numbers should not be regarded as surprising, as early development of the M1 was in partnership with Lamborghini.

Only 455 M1s were produced between 1978 and 1981, which breaks down to 399 road and 56 race cars. Relatively few examples were imported into the United States, and as such, they have always remained somewhat elusive on these shores.

SCM Analysis

Detailing

| Vehicle: | 1980 BMW M1 |

| Number Produced: | 453 (399 street legal and 54 race chassis) |

| Original List Price: | DM100,000 ($55,000) |

| SCM Valuation: | $88,000 to $165,000 |

| Tune Up Cost: | $500 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Left rear strut brace |

| Club Info: | M1 Register, BMW Car Club of America |

| Website: | http://www.bmwm1.org |

This BMW M1 sold for $242,000, including buyer’s premium, at RM Auctions’ Don Davis Collection sale on April 27, 2013, in Fort Worth, TX.

The M1. Even 30-plus years since it went out of production, most Bimmerphiles will still tell you that it is the ultimate Ultimate Driving Machine. To this day, BMW has not reused the name.

The McLaren F1? While having the heart of a BMW, it wasn’t marketed by BMW and it’s too exotic, too flashy and too damn expensive.

The M1 was originally intended to fight Porsche 935 and 936 cars in Group 4 and Group 5 competition — where Porsche was the 2,000-kilogram gorilla. Some also speculate that BMW wanted to show its chops as a world-class automaker with a supercar on par with Porsche, Ferrari and Lamborghini. Indeed, it was the latter company that BMW partnered with for chassis development on the project.

FIA required a minimum build of 400 cars to qualify for Group 4. In essence, the M1 was to be an assembled car with high-caliber components. In addition to developing the tubular space frame, Lamborghini was to construct it, while Italdesign fabricated the fiberglass bodywork. BMW’s largest contribution was a detuned variant of the fire-breathing 24-valve, 3.5-liter inline 6 that powered BMW 3.0 CSLs to the top of the European Touring Car series. ZF’s robust 5-speed transaxle would put the power to the ground — the same gearbox used for Group 4 cars and even the 950-horsepower turbocharged Group 5s.

It didn’t take long for the project to go astray. Lamborghini was constantly missing deadlines (this at a time they were on the brink of bankruptcy). As the delays continued to mount, some customers who put down deposits after the M1’s 1977 Geneva Auto Show debut pulled them.

A complicated assembly

To get the car into production, BMW ended their relationship with Lamborghini, and went to Marchesi of Modena for the tube frames. Italdesign assembled the bodywork to the frames and installed basic fitments, including wiring and the dashboards. The assemblies for street-legal cars were then trucked to Baur of Stuttgart for final assembly.

The last leg of the extended assembly line was shipment to Motorsports GmbH for final tuning, QC checks and delivery. With this convoluted process, it’s no wonder that the first customer delivery was in February 1979. Only the DeLorean — another wedge car from this era — was more dysfunctional during production.

If all this wasn’t bad enough, by the time the road cars reached customers, the requirements for Group 4 changed, and the M1 was no longer eligible. It was beginning to look like BMW had an albatross on their hands — a supercar built on a hoped-for racing pedigree, but nowhere to race it.

Jochen Neerpasch of BMW Motorsport is credited with creating a spec-race series in parallel with Formula One, which pitted the top F1 drivers against the top privateers. FIA agreed to it, and this became the Procar series. All but identical in concept to IROC in the United States, this was a race conducted before the main F1 race that put all drivers in identically prepped M1s. In theory, this was a test to find the best pure driver.

Procar was wildly popular among fans, and in a classic example of “race on Sunday, sell on Monday,” BMW sold 20 M1s immediately after the first Procar event.

An Autobahn bullet

Those 399 customers who eventually ponied up for a road-going M1 soon realized they had the ideal Autobahn bullet. The M1 had the handling and the long legs to make 160 mph, but the car was so reliable it approached mundane. This was a car that made going from Stuttgart in the morning to Lucerne for lunch possible — thanks to no speed limits and well-disciplined drivers on the Autobahn. As the ultimate touring car, this is perhaps where the M1 is most appreciated and fills its niche the best.

It was after the last M1 rolled off the convoluted production line in February 1981 that it finally had a chance to show its mettle on the track. Properly sorted, it was a force to be reckoned with in European Touring Car classes and IMSA in the U.S. during the early 1980s.

Elite among wedge cars

Looking back on the “wedgie car” years of 1975–88, the M1 is one of the few that comes off looking right. Fiat X1/9s, Pontiac Fieros, Triumph TR7s and Toyota MR2s are all too stubby. The C4 Corvette is too elongated. The Ferrari 308 family works pretty well. The Aston Martin Lagonda is just plain weird.

The M1 looks poised — a purpose-built tool used to commute via Autobahn rather than by jet. If one were to pick any nits, the pop-up headlights are the easiest targets — they are so 1980s — but that’s the way we were before high-output LED or Xenon.

The M1 became a cult icon early on. Even though none were officially imported into North America (or because of that), they were objects of desire for legions of male youths who put M1 posters on their walls. (I’ll admit it; I still have my Rod Caudell series poster of a Henna Red M1 that I got out of the pages of Car & Driver in 1980.)

Now that 30 years have passed, my age group is affluent enough to be a contributing factor on the M1’s renewed desirability — especially as the car was a bright spot on the dismal automotive landscape of our youth.

This example brought roughly double what a typical M1 would fetch a couple of years ago. They really didn’t depreciate — neither here or elsewhere — with the low ebb hitting around the same time as the dot.com bubble bust, when iffy examples could be had for $70k. Since then, values show a slow upward progression — as we’ve seen in higher-performance BMWs from the 1970s.

Last year, I watched this very car sell at the Mecum auction in Monterey for $196,100. The car seems to have been better detailed and had a set of Texas license plates on it, but it is essentially the same car as last August.

Getting an M1 registered in your state may or may not be possible — California is right out for this one because this car retains its Euro specifications. However, for someone with the resources to pay this amount for it, this is more of an inconvenience. Parts may be a bit of a challenge, but thanks to a close-knit group of fellow owners and strong efforts from BMW Classic, M1s are far more reasonable to keep maintained than any post-308-era Ferrari.

While one car doesn’t make the market, this does show that the M1 seems to have finally earned its respect in today’s collector-car market. It already has for those of us aligned to the blau mit weiss roundel. ?

(Introductory description courtesy of RM Auctions.)