SCM Analysis

Detailing

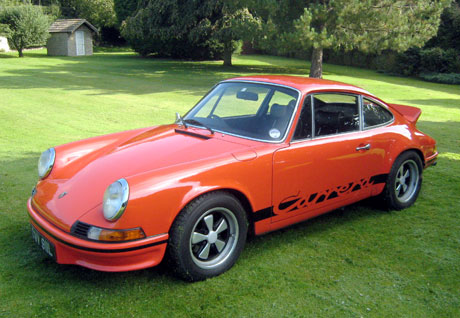

| Vehicle: | 1973 Porsche 911 Carrera 2.7 RS lightweight coupe |

| Years Produced: | 1973 (Lightweight RS) |

| Number Produced: | 200 (17 RHD) |

| Original List Price: | $11,000 |

| Tune Up Cost: | $500 |

| Distributor Caps: | $50 |

| Chassis Number Location: | Bulkhead just aft of gas tank |

| Engine Number Location: | Fan housing support on right side |

| Club Info: | Porsche Club of America PO Box 1347 Springfield, VA 22151 |

| Website: | http://www.pca.org |

| Investment Grade: | B |

This car sold for $345,400, including buyer’s premium, at the H&H auction in Buxton, England, on February 17, 2010.

One of the more interesting ironies of racing in the last third of the 20th century is that the most dominant production-based racing cars of the era are the variations on the Porsche 911, a car that was never intended to have any pretensions of being a long-lived race car, the early 911R notwithstanding.

When the time came to replace the 356, Porsche clearly understood that the requirements for a competitive racing car had diverged so far from those of a marketable street car that there was no point in trying to combine them. For a 356 successor, Porsche wanted to maintain the “Porsche shape,” and they were committed to having the engine somewhere behind the driver. But the idea of a mid-engined (engine in front of the transaxle) design simply wasn’t viable from an access and maintenance standpoint in a street car (it was 30 years before they thought Boxster).

Not intended for track use

The new 911 was thus built with something like 250 lb of engine weight hung behind the rear axle, which was acceptable for a sporting road car, but in Porsche’s mind eliminated it as a serious racing car. For that purpose they created the 904 through 917 series of mid-engined racers, which were hugely successful until the FIA changed the rules for 1973.

I’m not suggesting that Porsche didn’t entertain the idea of competing with the early 911s. They did well in rally and club competition in privateers’ hands, and in 1967 Porsche experimented with the 911R, but minimum production rules forced it to run as an uncompetitive prototype, and they only built 24 before losing interest.

International auto racing is controlled by rules set by the FIA, and for 1973 everything changed. Porsche had exploited a loophole in the 1968 rules: The 917 qualified as a Group 4 “sports car,” eligible for manufacturer’s championship points with a production of 50 cars, and it dominated the championship. But those rules expired in 1972.

From 1973, Porsche faced the real possibility of going from the dominant manufacturer to also-ran. Something had to be done, and the production classes looked like the place to do it, so Porsche’s engineers started looking at what could be done to make the 911 seriously competitive. If they could boost the horsepower, get the weight down, do something about all that weight at the back, and do it in a package that would sell at least 500 copies, they could have a very strong contender in the GT class.

Fortunately, tire technology had improved massively since the 911 was conceived. The first 911s used a 4½-inch-wide wheel both front and back. By 1973, the tires were available to put 9-inch rims on the front and 11-inch ones on the rear for road racing (6-inch and 7-inch for the street), thus allowing the rear weight bias to be handled by rubber on the road.

Add power, shave weight

Technological evolution helped with the horsepower issues as well. In the mid to late 1960s, a technique called Nikasil had been perfected. It is a nickel-silicon carbide matrix coating that allows pistons to run directly in coated aluminum cylinders, avoiding the need for cast iron liners. Porsche had used the system successfully in the 917 engines, and in the 911 it allowed bore to be increased to a 2.7-liter displacement. In the RS, this translated to an additional 30 hp over the 911S.

Weight was the toughest problem, but by going to thinner steel and glass, an aluminum subframe for the front suspension, and eliminating superfluous luxuries like door handles, the engineers managed to lose a very-significant 330 lb from the standard 911.

High-speed lift at the back was handled by adding a “ducktail” spoiler that both reduced lift and improved top speed by 3 mph.

By the formal RS introduction in Paris, the entire run of 500 that had initially been announced had been sold out, and Porsche ended up building another 1,080 of them. Most were the “Touring” version, less Spartan and a bit heavier than the “Lightweight.” It was the beginning of the longest, most dominant run of production-based racing cars in history.

With a relatively large production base, there always seem to be 15 to 20 911 RSs available for sale (both versions), and the value is well established. Condition, history, and originality are the primary variables, since most of them were used very hard. This car seems to have been known as one of the better ones, but not the best. The fact that it is right-hand drive gave a bit of an advantage for the specific U.K. market where it came to auction. The result is that it sold for just a little more than a left driver might have made, but within a very reasonable range. I’d say the sale was market correct for an excellent street example.