I live in a small house with a one-car garage that’s nestled within the confines of a bustling city, but I dream of owning a giant shop someday.

My mechanical wares swamp my existing footprint to the extent that I’ve already overtaken one neighbor’s garage, and I’m working on the other neighbor now. I do the best I can with what I have, but something has to change.

When a friend recently asked me why, I realized the answer is a bit more complicated than I understood.

Legend and purpose

You see, my grandparents lived in a hand-built farmhouse on a quiet country highway between nowhere and nuthin’. There were pecan (pronounced pee-kan) trees in the backyard, pine trees around the perimeter, and a four-bay shop out by the road. It was in that shop that my grandfather spent most hours of most days of the last few decades of his life, and it’s there that I picture him first whenever I think of him.

Much like my grandfather, the shop was worn and weathered and imposing on the outside — but it was solidly built, full of purpose and a marvel within. The simple cinderblock building featured a high roof, enormous sliding wooden doors flanking both sides, and a makeshift office up front. There was a gas pump sitting in the middle of the dirt driveway, but I can’t remember it ever working.

On the inside, there was a giant lathe that was always buried under a squishy pile of long, curlicue metal shavings that I remember thinking would make a nice, oily wig. There was a chain-operated hoist that would pluck engines out of giant trucks, an upright drill press that I used to punch random holes in chunks of two-by-fours, and a parts washer where dirty parts went in to be washed with dirty fuel and somehow came out clean.

The wooden workbench tops were soaked with oil and beat to a pulp, and the concrete floors were mottled with decades of drips and leaks and spills.

Farmers and truck drivers and little old ladies visited often, and it was their derelict equipment and dump trucks and Buicks that kept him busy. A lifetime of owning and operating heavy equipment and second-hand vehicles, an insatiable appetite for knowledge, and the deeply ingrained trauma of surviving the Great Depression influenced every repair he tackled. He wasn’t much for making a dollar, but the man could fix damn near anything.

A gathering spot

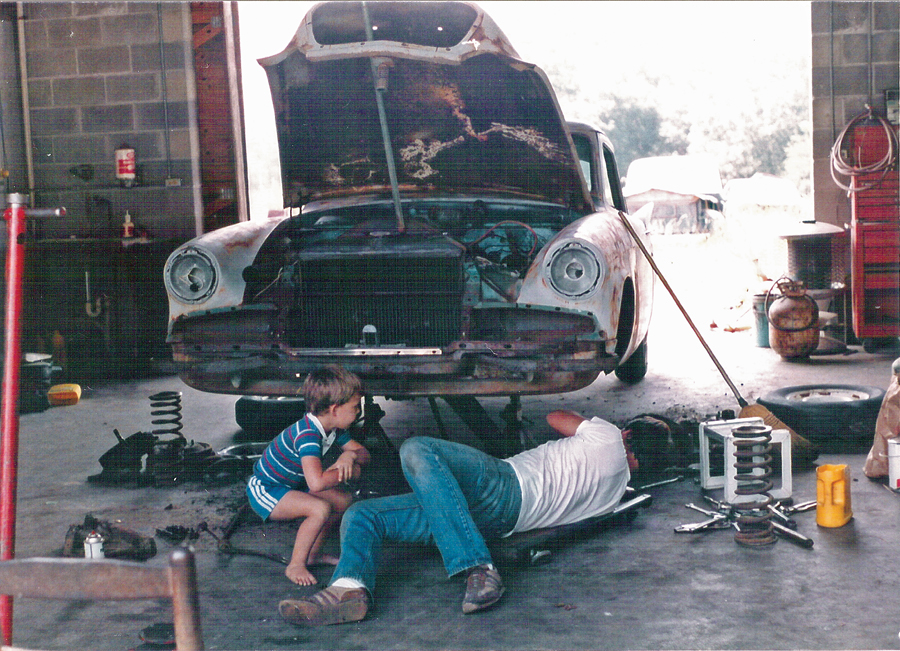

When the bay doors were open on the weekends, my dad and uncle could often be found out there in the mix with my grandpa. The three of them would fuss and laugh and grunt and cuss in the heavy Southern humidity while I crawled over bench seats and played in boat cabins and hit stuff with hammers.

I would open tool chests and ogle wrenches and pliers and sockets and ratchets, and I would ask, “What’s that?” and “Why?” until I wore out my welcome. Then I would wander off, pilfer a Coke from the vending machine, a packet of cheese crackers from the box on the front counter and wait for cars to drive by.

And when the work was done and the summer afternoon sun was low, I’d be sent to the old fridge hiding in the office for cold beverages. We’d sit on tires or plastic crates and, all of a sudden, no one was in a hurry to do anything. I didn’t really understand what was so great about just sitting and talking and having a gross ol’ beer after a hard day of dirty work, but it always seemed like the part of the day everyone had been waiting for.

On the best days, we’d push cars out of the way and sweep the floor and pull out an assortment of discarded old chairs. Cousins and aunts and uncles and friends would begin turning in from the highway, one after another. I would run back and forth between the shop and the house toting hot food and paper towels and fresh biscuits. A giant pot would be filled with water and placed on a propane burner that had been set up where a tractor had been having surgery an hour or two before. Steam would start sneaking out of the pot, and in went the crab and the shrimp and the corn and the sausage.

The men would all huddle around the pot and poke fun at one another and tell stories and laugh. The women would tell me to put shoes on and to stop sneaking mouthfuls before dinner was ready.

Eventually, the food would be served and over-consumed, and then the crowd would slowly disperse. The tables and chairs would be put away and the cars or tractors or boats would be pulled back inside, and, after the people had full bellies and happy hearts, those giant wooden doors would be pulled shut for the night.

Some years later, with heavy but thankful hearts, those doors would be pulled shut for good.

Going home

For some, a garage is a place to unload groceries without getting wet, and a workshop is a place to make things that could easily be bought or to fix things that could easily be replaced.

For me, those spaces mean a bit more, and the gnawing at my soul comes from way down deep. Those spaces remind me of where I came from, what I’m capable of, and of a man who I wish could see me now.