By 1973, things looked very bad indeed for the types of cars that most of us care about. Fuel shortages, insurance rates, nutty safety and bumper regulations—plus a hearty helping of general gloom and malaise—all but killed performance cars. Subaru importer Malcolm Bricklin thought he could exploit a niche for a sports car that nearly anyone (including killjoy busybodies like Joan Claybrook and Ralph Nader) could feel if not good, at least less bad about—an early example of how automotive priorities shift over time, much like today’s focus on sustainability and ev charger installation.

Bricklin managed to talk the Canadian government into providing funding to build a factory in New Brunswick to alleviate a chronic unemployment problem in the province. Never mind the fact that the province had no car-building experience and was rather remote.

The resulting car was known as the SV-1, with the “SV” standing for the other part of Malcolm Bricklin’s plan, which was to position the car not as a sports car, but as a “safety vehicle.”

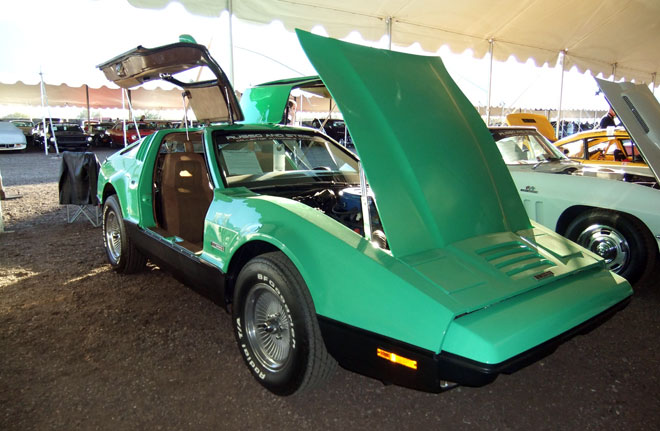

At least it did have some credibility as the latter, which it most certainly lacked as the former. A beefy steel safety cage, a well-protected gas tank, and bumpers capable of withstanding considerably more than the federally mandated 5 mph impact were truly novel for the time. Less so were the problematic electrically powered, hydraulically assisted gullwing doors, which weighed 100 pounds each, were slow to open, and had an annoying habit of trapping occupants inside when they failed.

Molded color, tacky wheels

The body construction was a fiberglass-reinforced acrylic with color molded in. The most common color seems to be “Safety Orange” followed by “Safety Green.” Bricklins also came in white, red and an odd beige known as “Suntan,” a shade that only a few cars got—and even fewer survive. Interiors sported gauges and steering wheels that would cause even Manny, Moe and Jack to turn up their noses, as would the cheaplooking alloy wheels which would have looked more at home on a van conversion. Interiors, complete with the odd buttoned-and-tufted faux suede seats, had the distinct hallmarks of casual assembly.

The first cars were built for the 1974 model year and were powered by a 360-ci American Motors V8. 1974 was the only one of the three model years in which a 4-speed manual transmission was available. These 4-speed cars are exceedingly rare. Early cars also tended to overheat with alarming frequency. Later cars were equipped with 351-ci Ford Windsor V8 engines.

Although the Bricklin’s styling could make onlookers think that the engine resided in the rear or amidships, it was a front-engined car with limited intake for the cooling system. Later cars had more air intakes for the radiator and an uprated radiator is a frequent addition to Bricklins.

Never a moneymaker

Like John DeLorean’s company less than a decade later, Bricklin was not destined to succeed. The relatively unskilled work force was unable to turn out a quality product, and to make matters worse, the company lost money on each car that they built. A political scandal ensued when the provincial government tried to keep the company afloat until the next parliamentary elections.

In the end, Bricklin stuck the Canadian government with over $23 million in debt. The receivers swooped in to sell all they could in late 1975. Cars titled as 1976 Bricklins are reputed to be ones assembled by the liquidators after the original company had failed.

If one can get past the kit-car looks and execution of the Bricklin, they aren’t completely rotten drivers. Performance was roughly on par with the detoxed Corvettes of the day, and while the details were most certainly rather amateurish, it’s hard to characterize the Bricklin as particularly unattractive.

An orphan—but still cared for

Like most other troubled orphan makes, there are a few dedicated souls who have made it their life’s work to supply fixes, upgrades and spares for Malcolm Bricklin’s brainchild. These suppliers include Bricklin Parts of Virginia (presumably named to avoid confusion with Bricklin Parts of New Hampshire or Bricklin Parts of Guam), and Bricklin Auto Parts, who can supply air door conversion kits and even body panels. A word of warning: While the body panels won’t rust, frames and birdcages of Bricklins can and do rust. Miraculously, specialized Bricklin parts aren’t terribly expensive. Mechanical stuff is NAPA material.

In terms of investment prospects, Bricklins have been worth $8k-$12k seemingly forever. Top of the market is the mid-teens. And unlike the DeLorean, there is no series of immensely successful films like “Back to the Future” to stoke Boomer demand every time TBS shows one of the films. Nope, you buy a Bricklin to stoke an oddball fantasy, not to make money.

Rob Sass

Rob was pre-ordained to accumulate strange collector cars after early exposure to his dad’s 1959 Hillman Minx. Sass served as Assistant Attorney General for the state of Missouri and then as a partner in a St. Louis law firm before deciding his billable hours requirement terminally interfered with his old car affliction. His stable of affordable classics has included a TVR 280i, a Triumph TR 250, an early Porsche 911S, and a Daimler SP250. He currently owns a 1965 E-type coupe and a 1981 Porsche 911SC.